Once Someone Appreciated My Words: An Interview with Mengyin Lin

Mengyin Lin is an exciting new voice in the art of the short story whose maturity and insight surpass her relatively recent dedication to the craft. “Magic, or Something Less Assuring”, which originally appeared in our Winter 2022 issue, recently won the 2023 Pen/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers. In celebration of her honor, she spoke with our contributing features editor Jamie Kahn about winning the PEN/Dau prize, her early encounters with literature, translating Chinese lives into English, and how fiction needs uncertainty.

Lin was born and raised in Beijing and currently lives in the US. Her work has been supported by the Tin House Writers Workshop and the Soho Fellowship, and appeared or is forthcoming in Epiphany, Joyland, Fence, Pleiades, and the New York Times. She holds an MFA in Fiction from Brooklyn College, where she won the Himan Brown Award, and a BFA in Film from New York University. In 2022, Lin’s short story was also selected for our 2022 Breakout Writers Prize.

JAMIE KAHN: What were your first encounters with literature growing up? What initially inspired you?

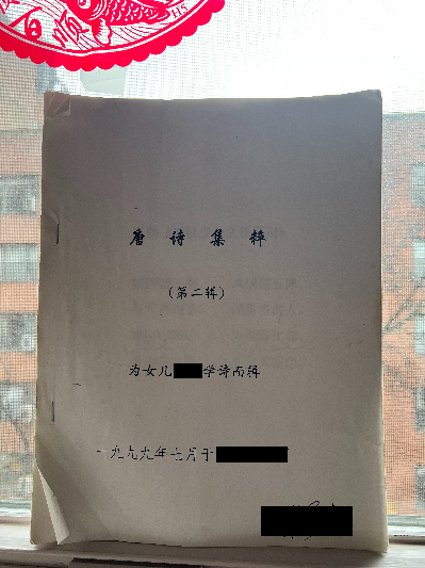

MENGYIN LIN: My first encounter with literature was probably ancient Chinese poetry, which was not uncommon for a Chinese kid of my background. Poems were in our Chinese textbooks from first grade and we had to recite them. When I was seven, my dad made a selection of poems and prose-poems (ci) and taught them to me at home. He printed them out and bound them into a small book, which, to this day, remains one of my most precious belongings. Few things are more beautiful than the imageries in ancient Chinese poetry.

I don’t know if any other country has this, but growing up in China, we read simplified, children’s version of what’s considered “the canon,” I guess? We literally call them “world famous books'' in Chinese, “world” meaning the Euro-American one, of course. The edition in my local children’s library had green covers with orange titles: Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Les Misérables, La Dame aux Camelias, Guilliver’s Travels, Little Women, and Crime and Punishment (!), to name a few. I read Chinese YA versions of these books in elementary school and have never read some of the originals again. I didn’t start reading fiction in English until I moved to the US at 18.

But those stories made such an impression on me as a child. Though now I see how limited of a world they presented, at the time they were beyond my reality, knowledge, and imagination. They taught me that I had the capacity to feel for other, people in times and worlds that were not mine, through language; they taught me what books could do.

“When I was seven, my dad made a selection of poems and prose-poems (ci) […] into a small book, which, to this day, remains one of my most precious belongings.”

With the experiences and growth you've made so far as a writer, do you find your initial inspirations have evolved?

I only started writing fiction in late 2020. I had always thought myself as a reader, not a writer. Literature was too good for me. I didn’t dare write fiction in Mandarin, not to mention my second language, English. I started writing because going through the pandemic in the US made me realize that a lot of people in the English-speaking world, in America at least, don’t have any idea who Chinese people are today, and have very little, or even wrong, understanding of my generation, who are vastly different from previous generations (similar in many ways, too, surely.) Having been in the States for a decade then, I had always known this reality piecemeal, but the pandemic really shoved it in my face.

That was the initial inspiration. But the more I write, the more I realize that I am not writing to be understood, but more to understand ourselves and the shapeless contradictions that are our life, to make meaning in the process of—unknowing? I can’t really articulate it.

Another thing that has changed since I started writing is that I now understand that I don’t have to, and cannot, write like writers I admire. I’m never going to be as good as they are at what they do. I can only write like myself, and with every story I’m discovering my abilities and limitations. Accepting this has made reading much more enjoyable, too.

How did you first conceive of the "Magic, or Something Less Assuring"? What was the process like of growing that story?

I wrote the story in October 2021. At the time, a reality show called See You Again was very popular in China. The show followed three couples, who struggled with their marriage, on an 18-day trip. I heard about it on a podcast but never watched the show. Before that, I had been thinking about the new divorce policy China introduced in December 2020 to lower the divorce rate. It’s called the “divorce cool-down period” [and during it] a couple applies for a divorce, waits for at least 30 days, and both parties must be present again at the same time to finalize the divorce. Either party can back out of the divorce during this period.

Ting and Si-Bo are the grownup versions of two characters in a screenplay that my friend and I never finished writing. Once I decided to write about them, I knew I wanted to inhabit both of their perspectives. It’s easy to write someone whom you agree with; the other way around is much more challenging.

I think that’s what fiction gives space to—to be outside yourself. If we can try it in fiction, we may be able to try it in life. Since early 2020, I had fought with a few close friends and family about how China (and the US) handled the pandemic. The pandemic convinced many Chinese people that China’s political system was superior, China was the safest place on Earth, and everything that the government did needed to be done. In many ways China handled the pandemic so efficiently before Omicron and that success came at a cost that people were willing to ignore. It was a time that I felt the reality as I knew it was beginning to shapeshift, cracking open and coming apart. We live in such divisive times and so often we find our closest ones on the other side of what we believe is just or true. But love doesn’t simply vanish between people because of that; love complicates things as it should.

So I thought it would make an interesting journey to send Ting and Si-Bo, who hold different political opinions, on a divorce honeymoon during the “cool-down period.” But where to? There are only a handful of countries that Chinese citizens can go without a visa. Morocco, being one of them, has grown very popular among Chinese travelers. I had been there twice: once with my partner and once on my own. It was the last place I visited before the pandemic, so it was fresh on my mind. I wanted to see what an unfamiliar place and culture would do to how [a couple] saw each other and their relationship.

Finally, the title came from Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s film, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, which I had just seen at the New York Film Festival. In the film, magic refers to many things: the feeling of being in love, the chemistry between two people, coincidences, etc. all of which guided the story beneath the surface. I liked how precarious this title was, unsure of itself, just like magic, so I stole it.

“I wanted to see what an unfamiliar place and culture would do to how [a couple] saw each other and their relationship.”

You mentioned that you prefer Mandarin in speech. Is English the language you prefer writing in? Do you find that writing in English affects how you explore the lives of your characters?

I prefer speaking Mandarin because I feel more confident in it. Even now, I am afraid of making mistakes and constantly do when I speak English. In addition to pronunciation, tense (which forces time to be linear and Chinese doesn’t have it) is difficult; he/she are pronounced the same in Chinese (Chinese originally only had one pronoun for all humans, which was so amazing! the female pronoun was only coined in 1918) so I often misgender, like I would switch gender suddenly in the middle of telling a story and confuse people. Numbers are also really hard to convert because Chinese uses a different numeral system. I like making jokes in Chinese and for a long time I didn’t know how to do it in English.

But I self-censor in Chinese. Because I learned it as a censored language and have only used it within a censored society, I don’t know how not to. And there’s the practicality of it, too: it’s impossible to publish a lot of the stories and characters that I’m interested in had they been written in Chinese. It’s liberating to write in English, but in speaking I find it a colder language than Mandarin. I hope to write fiction in Mandarin someday.

[Writing in English] operates at a distance from my rawest emotions and allows me to think more clearly. I [also] want readers to be aware that my characters are speaking Mandarin or a dialect. I want them to know from my prose that English is my second language. It only became the dominant language of my life at 18, so in a sense I came into adulthood in English.

I don’t know how exactly writing in English affects the lives of my characters, but I am suspicious of it. Is it really possible to write stories in the language that the characters within them don’t live with and sometimes don’t speak at all? Does it throw authenticity into question? Or perhaps authenticity is not what I’m after. Truth??? I’d love to hear from other second language writers.

What does winning the PEN/Dau Prize mean to you?

My first reaction: the little story that I wrote in my first semester of MFA has gone so far—how wild! I wish I were cool enough to feign nonchalance, but I’m really not. It gives me a chance to share my joy with friends and teachers who have supported me so much since I started writing and give them my gratitude. Happiness is one of those things that the more you share with others, the more you have yourself. A mathematical miracle.

It’s such a special prize because one only debuts once! I feel incredibly lucky. Not much else. I’m just looking forward to more people reading this story.

There’s so much work that deserves recognition, so I don’t take this lightly. Any recognition undeniably feeds the ego, like an injection of pure pride. Then my mind starts to metabolize it, and by the time I sit down to write again, it feels like I’ve just come down from a high, and the usual suspects make their return: self-doubt, fear of failing, blah blah. Winning this prize means that when writing gets difficult, which it inevitably will, I can remind myself that once someone appreciated my words.

“Happiness is one of those things that the more you share with others, the more you have yourself. A mathematical miracle.”

You recently wrote an opinion piece for the New York Times. Is non-fiction something you are interested in pursuing further? For you, is it connected to the subjects you explore in fiction?

I am not sure if I’m interested in pursuing nonfiction! Besides personal statements for various applications, the essay for the Times was the first time I wrote about myself as myself, unmasked. In the process of writing it, I realized that some fundamental things about nonfiction, or this subset of nonfiction (opinion essays), were against my instinct as a fiction writer:

First, an opinion essay makes a clear and decisive argument, and, I think, fiction aims for the opposite. Fiction questions, muddles, mystifies. When I was writing the essay, as soon as I wrote a statement, I wanted to backtrack and poke holes in my own argument. A great number of fiction writers bring their curiosity and ambiguity into their nonfiction and I love reading them, so this might just be my being inexperienced. It is difficult to take a stance in writing and in life. This is certainly not to say that fiction doesn’t have moralities, but that’s too much to get into here.

Second, the nature of nonfiction intimidates me—why should anyone care what I think or what happens in my unremarkable life? Even as I’m giving these answers here, a voice is telling me that they are too long, that I should shut up.

Somehow, I have so much more faith in my fictional characters. I believe that their stories deserve to be told, to be read, and I am only the conduit for them to speak to the world. This also sounds pretentious, as if I don’t just make them up. So I don’t know! But immediately after finishing the essay, I started a short story about the same protests that I mentioned in the essay. In the world of the story, I felt comfortable and confident as a writer. Perhaps it’s just my cowardice? Some people said that it was brave of me to write the Times essay. Can writing fiction be brave, too?

[But] hearing from people, especially young Chinese readers, made me see the power of nonfiction. And that’s enough to keep me writing. Perhaps obsessively worrying if my opinion deserves to be heard is self-absorbed, self-important, too. Perhaps it’ll be okay if I only write nonfiction when I feel that I have something to say and not saying it would compromise my being. Because in many circumstances, silence can be dangerous, menacing; silence is complicity.

Are there any contemporaries that particularly inspire you? Who do you think everyone should be reading right now?

The most memorable English fiction I read in the past year were Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English and Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife. I think both writers are also poets? There’s something so direct and precise about their prose and the emotionality in their narratives. Their characters occupy such complex, powerless yet powerful perspectives that confronted me as a reader. I also loved Cristina Rivera Garza’s story collection from Dorothy Project. I admire how she writes about women and femininity and how the specificity of a culture, a history, a place comes through without being named.

Another one is the debut short story collection, The Submarine at Night (夜晚的潜水艇), by the Chinese writer, Chen Chuncheng (陈春成). I don’t think it’s translated into English yet. I felt free, momentarily, to be immersed in his imagination.

But if we are talking about what EVERYONE should read, fiction may not be my first choice. I’d say read Hannah Arendt and Thích Nhất Hạnh.

What are you working on right now?

I’m writing what I hope are the last two stories in my short story collection, which is about the One-Child generation that I’m a part of. In the meantime, I’m revising and cohering the rest of the stories in the collection.

I’ve spent quite some time in my head with a few characters that I think belong to a novel. But until you start writing, a novel just seems like an infinite idea that gets more and more daunting by the day…So I recently pushed myself to see what these characters look like on the page, chiseling away at this abstract infinity to something concrete and finite, word by word. I’m truly excited to learn more about them and their world.

What I’m really working on: recollecting distant memories, conversing with tarot cards, and occasionally trying to be without language.

Jamie Kahn is the contributing features editor at Epiphany, and has written for Glamour, Brooklyn Magazine, Huffpost, The Los Angeles Review, Epiphany, and others.