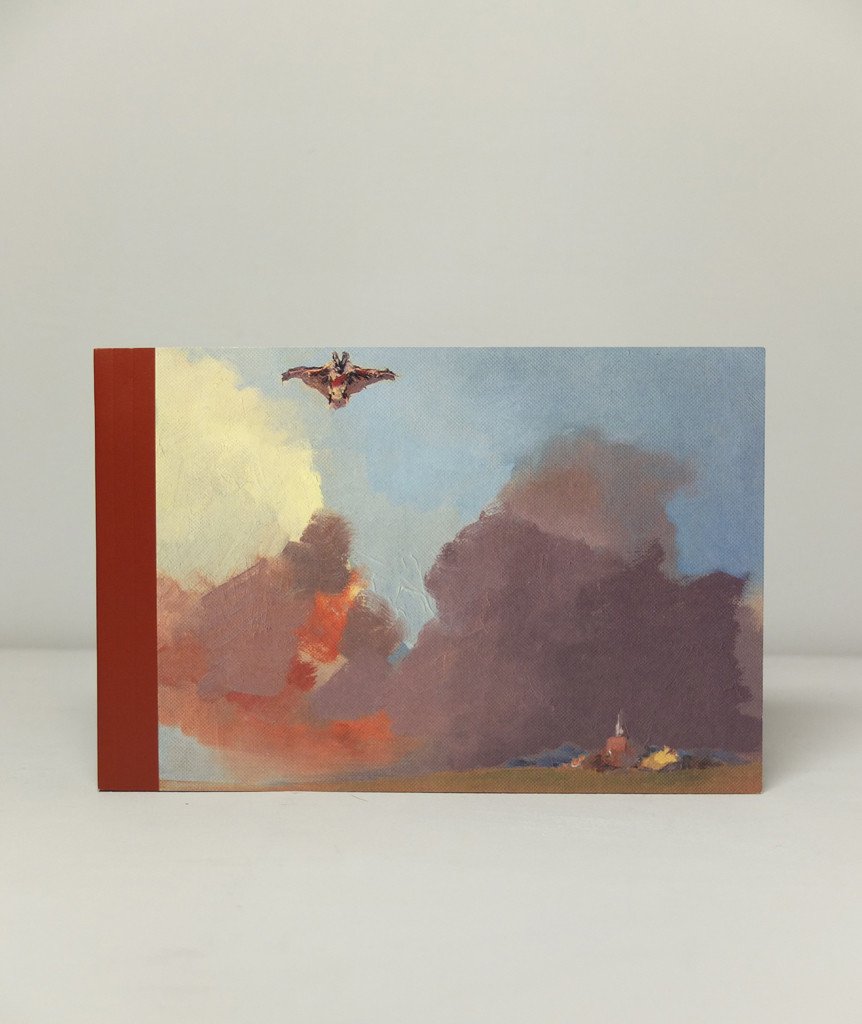

Monster's Bat

by Siena Oristaglio

How much of fear is myth?

I’m in Central Park at dusk.

It’s mid-October.

The evening air tingles against my cheeks.

I’m seated on a large rock in The Ramble,

a woodland area of the park,

overlooking a lake.

Couples glide past sleepily in rowboats.

A group of nearby teenagers chatter

in French about a flock of geese

that preen and flap around them.

I stretch my boots towards the water.

In my lap sits a small book called Bat Opera.

It contains reproductions of paintings

by British artist Monster Chetwynd.

I flip through its pages.

They teem with rocky landscapes,

orange clouds, broody skies.

Some paintings display close-up

portraits of bats in action, their faces

open and contorted or silhouetted in profile,

gazing up at an unknown curiosity.

Others show far-off flocks of

black-winged creatures exploding from

the side of a mountain or vanishing

into clouds smudged by wind.

The artist has been painting this series of

small, vibrant bat studies since 2003

and she plans to do so for the rest of her life.

In an interview, Chetwynd describes her fascination:

“[Bats] have the stigma of evil.They are perfect as unworthy subject matter.

Early on I had a quick recognition that I could use

them as comic anti-heroes.

That classic tension in painting between

repulsion and attraction… Within painting discourse

this can be dubbed simplistic, but for me,

this makes them great subject matter.”

Studying the enormous ears of a glowing

red bat curled on a cloud,

I’m inclined to agree.

A goose squawks and I look up.

The sky has turned from pale gray to a light pink

that could have been splashed straight up out

of one of the paintings in my lap.

I scan the tree line across the lake, searching

for a glimpse of one of Chetwynd’s subjects.

Multiple species of bats are known to frequent

this area just after sunset during summer

months and into the fall.

I’m hoping that enough have not yet gone

into hibernation so that I can spot a bat or two

as they come out to seek their nightly prey.

I study the underside of the two bridges

in sight known to be popular roosting spots.

No signs of motion.

I turn back to Bat Opera and flip the page.

A lone bat, its wings outspread and illuminated,

plunges through a black backdrop towards

the whisper of a crimson cloud.

From Bat Opera

I trace its translucent wings with my finger.

Then I touch the darkness.

.

Why does the liminal produce fear?

In describing why bats are commonly

associated with the Halloween season,

journalist Erika W. Smith cites history

professor and folklorist Steve Siporin:

"One of the main themes of Halloween is liminality —

the in-between-ness,” Siporin relayed to Popular Science.

“There are all sorts of symbols of that in-between-ness.”

Bats are one such symbol.

As the only mammals that can fly, they are often

imagined as something not-quite-mammal,

a species dancing in the liminal space

between bird and rodent.

I call to mind other subjects of fear that abound

during this season: ghosts, zombies, mummies,

demons, werewolves, monsters, vampires.

I reflect on the in-between-ness of each.

Dead + Alive.

Dead + Undead.

Human + Wolf.

Human + Other.

Human + Bat.

I imagine all the fear these creatures

have produced hissing in a steel cauldron.

I add to this cauldron the violence faced

by my own loved ones who live in the in-between —

those, like myself, who exist in liminal genders.

Why is liminality terrifying to so many,

I wonder, when we see it everywhere, every day?

The sky now shifts from light pink to a blue-ish orange.

Dusk.

Day + Night.

In another Bat Opera landscape,

a swarm of black specks

emerges from a backlit cloud,

forming its own stormy cumulus.

Bat + Cloud.

I inhale and hold my breath in my lungs.

I sit in this moment of pause and turn

back up to the sky.

My eyes catch on a frenzied speck

in the distance: a bat!

Excited, I press my hand roughly into

a divet in the rock beneath me.

Hand + Rock.

I lean forward and squint my eyes.

The bat swoops and dissolves into a distant pine.

Bat + Pine.

I exhale.

.

How does a close encounter with a feared subject alter the fear?

In 2008, Australian scientist Dr. Jack Pettigrew

described a recent cave art discovery:

“The depiction shows eight roosting

megabats (flying foxes) hanging from

a slender branch, or more likely, a vine.”

(Photo credit: Jack Pettigrew)

The drawing has since been dated to

the height of the last Ice Age —

somewhere between 20,000 and 25,000

years ago — proving a fascination

with bats is both ancient and new.

One painting in Bat Opera bears

striking similarities to this ancient art:

in it, three bats hang upside-down

on a branch in a quiet huddle.

From Bat Opera

Gazing at the inverted creatures,

I recall my trip to Paramus,

New Jersey, earlier in the day.

At a small strip-mall shop called

Wild Birds Unlimited, I had the

pleasure of watching two megabats

named Arnold and Luna devour

a cantaloupe upside-down.

While the creatures snacked,

a chiropterology expert named Joseph D’Angeli

peppered us with pleasant facts about bats:

“Bats are among the world’s most naturally gentle animals.”

“We wouldn’t have tequila were it not for bats, as

agave plants only open at night and rely on

night pollinators to reproduce.”

“Vampire bats are about the size of an ice cube and

are extremely shy.”

“Bats can live up to 41 years.”

“Bats in some species will give their food to other hungry bats

even if this act brings about their own starvation.”

Myself and those in the room were surprised

to learn many of these facts.

Perhaps surprise at finding relatability

and gentleness in such feared creatures

accounts for the hundreds of thousands of views

that videos of bats eating fruit have garnered online.

I take my own video of Arnold and Luna munching

on the cantaloupe and send it to a friend.

Who knew bats were so adorable, he writes back.

.

How do we teach love for the liminal?

One of the final paintings in Bat Opera

depicts an extreme close-up image of a bat’s face.

The bat is furry, sleepy, and appears very young.

Its eyes glint with an infantile sweetness.

From Bat Opera

Painted on its forehead are two white markings

that closely resemble the marks on the bats

in the cave drawing.

This same species of megabat has existed for

at least tens of thousands of years.

Ancient + New.

I close Bat Opera and begin my walk towards

the park exit, pausing on Balcony Bridge to

remind myself every bridge, too, is a liminal space.

The sky is nearly dark now.

I suddenly wonder how many bats hang under me,

preparing for their nightly adventures.

I press my face to the concrete railing and listen.

Leaves rustle, caught in currents of wind.

Wind + Leaves.

Drops of water fall from a bushy overhang and melt into the lake.

Waterdrops + Lake.

I close my eyes and inhale.

Lungs + Air.

Then I make a sound so loud it can be seen.

Siena Oristaglio (all pronouns) is an artist and educator. She co-runs The Void Academy, an organization that helps independent artists thrive. She lives in New York City.