The Abyss Munches Back: On Martin Amis’ INVASION OF THE SPACE INVADERS

by Sean Gill

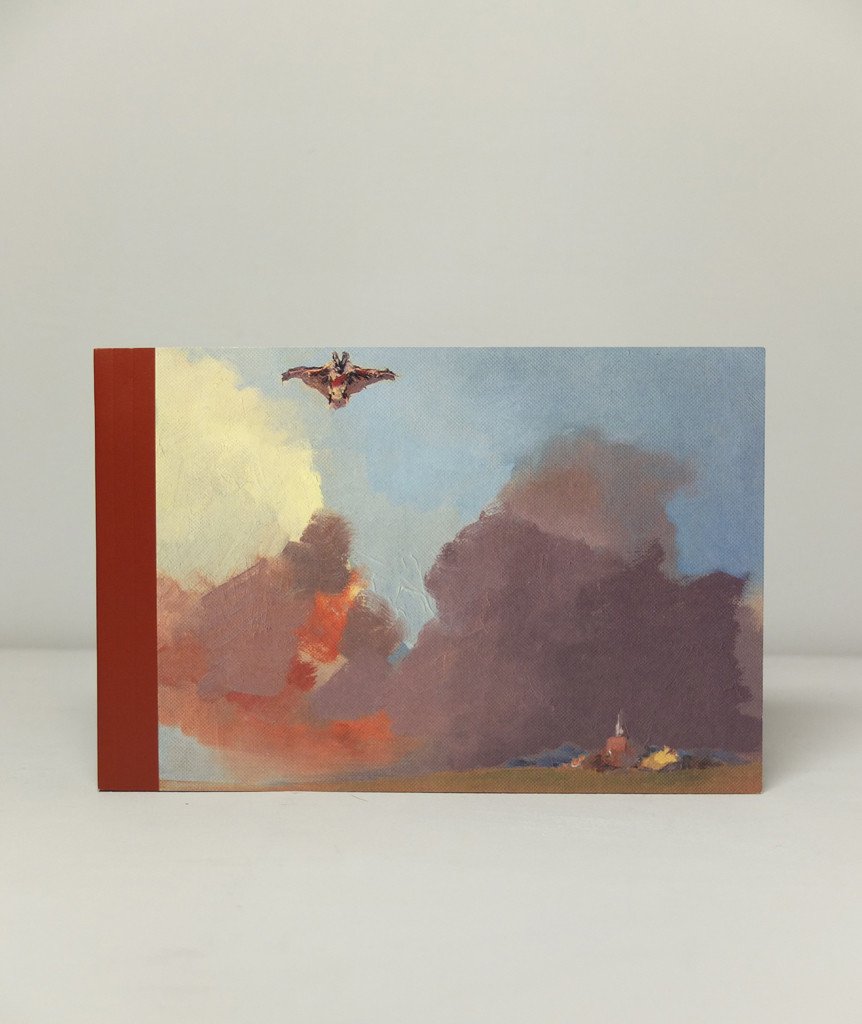

The cover of Martin Amis’ Invasion of the Space Invaders: An Addict’s Guide to Battle Tactics, Big Scores, and the Best Machines really sets a tone. A vaguely cyberpunk/rockabilly Flash Gordon-looking minion leans rakishly against a generic arcade cabinet while a green-eyed Space Invader looms in the background. Leafing through the first pages, you will find this image is soon mirrored by a photo of Steven Spielberg (!) affecting a similar pose against a Missile Command cabinet. In his brief introduction, Spielberg describes Amis’ brain as “seething with little green monsters, lemons, smart bombs, boulders, and fatboys”(1) and teases “Martin’s horrific odyssey round the world’s arcades.” The book that follows is divided into three distinct parts: the first, a relatively sober examination of the video arcade phenomenon; the second, a detailed blow-by-blow strategy guide for defeating games like Defender and Pac-Man; and the third, simultaneously a dystopian narrative about addictive video games invading the home and a Sears Wish Book-style advertisement for those very same products.

Once you get over the initial shock and guffaw that literary royalty Martin Amis wrote a 1982 book about arcade games, you can access further dimensions. This work of journalism doubling as a humorous piece of pop culture ephemera provides a dark window into a mind ruffled by dissatisfaction with Hollywood, the same one that would soon deliver the author’s most-celebrated novel, Money: A Suicide Note.

Cover art by Mick Brownfield

It once seemed to be common knowledge that Amis was mortified by Invasion of the Space Invaders and probably played a role in taking it out of print (where it assumed kitsch-holy-grail status alongside other rarities like Madonna’s Sex and Richard Curtis’ novelization of the film Halloween).(2) The formerly rare find’s subsequent reissue in late 2018 by Jonathan Cape and a contemporaneous interview in the Times of London revealed an Amis now capable of acknowledging the work, though claiming not to have read it in “decades.” The interview goes on to reveal that, while you can take the Amis out of the video arcade, you can’t take the video arcade out of the Amis: a raw passion remains, quick to express strong opinions on the stupidity of Frogger and his adoration of Defender.(3)

To clarify, Invasion of the Space Invaders does not figure as mere juvenilia; when it was released, Amis was thirty-three and had already published four novels. His name is proudly emblazoned on the cover, and his author’s bio promotes the 1981 novel Other People: A Mystery Story, as well as his work as Literary Editor of the New Statesman. He employs a version of the same bitter, mock-serious tone his readers would have recognized from Dead Babies and Success. Eventually, it becomes clear that Amis is as genuinely delighted by video games as repulsed by them, and that, had his feelings not been in such furious and fretful opposition(4), he likely wouldn’t have written the book.

He’s simultaneously above the idea of the video arcade (“Not many people in here look normal, well-adjusted, and human, like me”) and below it, as his enthrallment becomes that of a habitué and addict (“Oh, the shame and guilt. Oh, how you have to cringe and hide!… The lies increase in frequency and daring. Feelings of self-disgust assail you”). The programmers of the games (including “Atari’s Steve Jobs,” who is quoted on the connection between computer programming and metaphysics) are at first revered as techno-demigods, more ingenious than their equivalents in the military-industrial complex. Later, they are reduced to “video eggheads,” an insult Amis employs no fewer than four times.

Nearly all aspects of Amis’ video game addiction are sexualized. After vanquishing Space Invaders, he prowls the seedy arcades of Times Square, moving on to “fool around with a whole harem of newer, brasher machines.” He aligns the habit with pornography (“no worse than any other form of selfish and pointless gratification”) and claims to have witnessed a boost in child prostitution relating to the arcades: “Kids are coming across for a couple of games of Astro Panic, or whatever.”(5) He captions the photo of a man with a wide stance playing Space Invaders with, “Note the shoulder-work and buttock-heft that go into being invaded.” The latter levels of Defender grow “faster, tighter, nastier” and Asteroids requires a violent “spray action.” To him, video games are apparently zero-sum, with the winner or loser (whether human or computer) sliding into the category of either dominant or submissive (he takes a particularly assertive pleasure in beating a chess simulator). Yet, even if the human player reigns supreme, addictive play becomes an invasion of the mind, a violation. Continued use descends into robotic harlotry as you’re “hooked on the radar, rumble, and wow of friendly robots who play with you if you pay them to.” When Amis contemplates the rise of household video game consoles, the prospect almost seems akin to urban vice creeping out of the bordello-arcades and into the suburban bedrooms of God-fearing citizens: “the green monsters will have forced their way into every self-respectably affluent home… the Invasion will then be complete.”

Martin Amis in the early 80s (photo source: Ulf Andersen, Getty Images)

If Amis’ relationship with video games is punctuated by momentary gratification and lingering distaste, so too, perhaps, is the reader’s relationship with this volume. On the one hand, we have the glorious, nearly lovable spectacle of Amis panning Cosmic Alien (“How has this feeble wreck survived? Someone up there—a cosmic alien, maybe—must like Cosmic Alien”), designating Lunar Lander as “for gentle old hippies,” accusing Centipede of likely ushering in “new games called Dry Rot, Pest Control, and Earwig,” and addressing Donkey Kong directly: “Donkey, your days are numbered. The slaughterhouse yard awaits you.”(6) He compares Atari’s Tempest to the finale of Kubrick’s 2001, quotes E.M. Forster in relation to Space Invaders,(7) and even sneaks in a few Nabokov references.(8) He praises Asteroids as “one of the more mystical of the video games” and signals his intent to “start work on a cult bestseller entitled Zen and the Art of Playing Asteroids.” He gushes over “those cute little PacMen [sic] with their special nicknames, that dinky signature tune, the dot-munching Lemon that goes whackawhackawhackawhacka: the machine has an air of childish whimsicality.”(9)

In contrast to this good humor, Martin too often lives up to the ill-tempered chauvinism of his notorious and adversarial father, Kingsley. He drops homophobic slurs and unnecessarily defines one in his glossary as meaning “gay,” which, to this reader, only magnifies its mean-spiritedness. He refers to a group of black teenagers as “all gone on ganja, dreadlocks, and petty crime.” He advises against imprecise strategies in Asteroids, warning “you’ll find yourself dodging bricks, and will be stoned to death like an Iranian rapist.” The book itself spasmodically repulses its readers and possesses the same strand of noxious unlikability that pops up like a poison trail through much of Amis’ work.(10)

But how did Amis get here, grumbling among the “pallid addicts [who] loiter and dangle like mutated bats?” By placing Invasion of the Space Invaders in a wider biographical context, I think we can untangle a few inherent threads of meaning.

As he describes it, Amis’ gaming origin story places him at a bar near the railway station in Toulon, France during the summer of 1979. He plays his first round of Space Invaders there, which leaves him “ravished, transfigured, swept away.” He is the last to leave the bar that night after many fevered hours of obsessive play. What put Amis in this mindset? Perhaps it was fallout from his work on Saturn 3, the notorious sci-fi train-wreck starring Kirk Douglas, Farrah Fawcett, and Harvey Keitel, a film whose implosion arguably led to the death of its creator and original director, John Barry(11), and ensured Amis’ name would not accompany a screenplay again until 2018, when he adapted his novel London Fields.

Saturn 3—a film notionally about a robot that looks like a headless version of H.R. Giger’s Alien(12) and that happens to be powered by fetus brains (yes, really), which energy it uses to terrorize Farrah Fawcett—would have been wrapping principal photography around the time Amis had his first run-in with Space Invaders. With his collaborator John Barry recently passed on and his not-yet-released Hollywood debut already becoming an object of ridicule, one can imagine the mindset that led Amis to join the “clandestine brotherhood” of these “sinister machines” on a multi-year bender. The armchair psychologist might see the sci-fi trappings and robotic enemies as triggeringly reminiscent of Saturn 3, and the childlike setting of the arcade as a kind of transgression against a father who surely would have derided Pac-Man and Defender as infantile.(13)

It seems likely to me, anyhow, that, after writing the Kafka-esque amnesia labyrinth Other People (released in summer of 1981), Amis had yet to exorcise Saturn 3’s demons—and the perfectionistic pursuit of video gaming (along with validation from a master of profitable science-fiction, Steven Spielberg, and plausibly some kind of monetary kickback from the gaming industry) left him able finally to move on and process the full depth of his Hollywood experience through Money.(14)

“Money,” writes Amis in Invasion of the Space Invaders, “has never looked cheaper. It looks disposable, throwaway stuff.”

In other words, look too closely into the coin slot on an arcade machine, and you may glimpse a particularly Amis-esque abyss.

Sean Gill is a writer and filmmaker who won Pleiades’ 2019 Gail B. Crump Prize, The Cincinnati Review's 2018 Robert and Adele Schiff Award, the 2017 River Styx Micro-Fiction Contest, and the 2016 Sonora Review Fiction Prize. He has studied with Werner Herzog and Juan-Luis Buñuel, documented public defenders for National Geographic, and other recent work may be found in The Iowa Review, McSweeney's Internet Tendency,and Michigan Quarterly Review.

(Above image by Phil Dobson)