Two Novels, Fat and Thin: Keith Gessen’s A TERRIBLE COUNTRY and Ryan Chapman’s RIOTS I HAVE KNOWN

by J.T. Price

“Everything’s Revolutionary Now”

“Oh, Andryush. You haven’t learned anything about this place, have you? You’re still such an American. You still believe in words.” — Yulia Semenova, close companion to Andrew, or Andryush, an American in Moscow

The 2018 release of Keith Gessen’s A Terrible Country couldn’t have been better-planned, in a way: since the early ’90s, Russia has rarely received more airtime on U.S. newscasts than in the aftermath of November 2016. Notoriety and fame being, for all intents and purposes, impossibly confused by today’s media hothouse, it stood to reason—if reason applies (it probably doesn’t)—that Gessen’s novel would benefit from such itchy topicality. On the other hand, perhaps A Terrible Country couldn’t have been timed any worse: in the face of insatiable, some might even say, unseemly hunger for reports on Russian subterfuge—virtual cloak-and-dagger stuff executed, we might imagine, with knowing smirks and callous laughter—here is a novel essentially concerned with a sweet, well-meaning innocent and his estranged grandmother in Moscow. Unlike our narrator’s family of naturalized American citizens, she never left Russia. The only problem with this as subject matter is what it leaves out: wherefore the nefarious Russians?

Well, there are a few. Our Moscow correspondent, Andryush, known in New York City as Andrew—his grandmother, “Baba Seva,” first refers to him when he arrives at her door as “Andryushik”—encounters plenty of steely demeanor from passersby in 2008 Moscow. The city streets and boulevards are laid out by Gessen with great care; The Coffee Grind, Andryush’s all but daily refuge from living with his grandmother, sits across a boulevard from FSB headquarters and the dark basements known to the historically minded as the sites of mass executions under Stalin. A would-be professor seeking any possible foothold in academia, Andryush cannot help his own historical mindedness, so is naturally one to appreciate the irony of a shiny, wifi hub hawking absurdly overpriced pastries to the figurative (and in some cases literal) descendants of those blunt-minded killers. But at The Coffee Grind, nobody bothers Andryush much, certainly no intelligence officers, despite the self-regarding grandiosity of his allegiance to leftist causes; he’s a Westerner dedicated to bringing about a dramatic economic and societal shift—even in a country not technically his own! Someone must care about that, no?

The answer is ‘not really.’ At least not at first, except for a small reading group of like-minded native Russians that go collectively by “October.” It’s only at the hockey rink Andryush visits for exercise and kicks that opposing players veer at times toward the vicious; only outside a nightclub after a long night out carousing on as little money as possible that he’s pistol-whipped for speaking with the wrong woman; only from the mouths of elderly women on a park bench near his grandmother’s building that he’s treated to casually shameless anti-Semitism. Baba Seva had warned him about who these women were, but seeking new acquaintances for his grandmother in the face of her growing isolation and senility, Andryush chooses not to believe her without confirmation.

And confirmation is what he gets.

A Terrible Country, though, is not a novel meant to stigmatize modern-day Russia from some lofty Western perch—if anything, the implicit critiques of one society (overbearing misogyny, repressive policing, marginalization of leftist initiatives, a wild and often outright thuggish real estate market obsessed with the veneer of gentrification) have only surged more undeniably into view in the good ol’ U.S. of A. since Gessen started work on his novel. Struggling to decide the degree of his allegiance to the land of his ancestors, Andryush draws comparison between life in Moscow and in New York City: “What in New York took twenty minutes, here took an hour. What in New York took an hour, here took pretty much all day. It wore you down. The frowns on the faces of the people wore you down. The lies on the television too, after a while, wore you down.” In 2008, recall, the pre-Hurricane Sandy subway still ran fairly smoothly, whereas what might have taken twenty minutes then seems to take an hour today. So… so much for that comparison.

And we have our heaping share of lies here, too, don’t we? As much as Russia was “westernized” in the early ’90s, perhaps the United States under its dubious TV star president is now being “russian-ized.” Though, again, Russia as portrayed by Gessen is not a terrible place, or not exclusively so, and if terrible, then in ways an American ought readily to understand. As might be expected of a novel by a founding editor of intellectual journal n+1 (a.k.a. Bourdieu Does Brooklyn), A Terrible Country is vested in the material realities of being young and ambitious and outside the inside track. Among the young and relatively impoverished in Moscow, Andryush finds a refreshing earnestness of thought and desire to connect—“connect” not in the sense adulterated and made thin gruel by corporate America but genuinely, without ulterior motive. The quality that these earnest readers exhibit stands in marked contrast to the naked careerism, the veneer of fellowship, exercised by Andryush’s academic rival, the “delightful” Russia expert Alex Fishman, whose visit to Moscow is the occasion for some disruptive and ultimately rewarding behavior by Andryush.

There is more: Dima, Andryush’s wolfish older brother, is an entrepreneur driven from Russia for getting on the wrong side of the ruling elite; various other subplots, in particular one concerning a dacha (summer house) in the country, revolve around the cast of Russian characters who play on Andryush’s recreational hockey team; and, consistently, the novel returns to the comedy and pathos of Andryush caring for Baba Seva, while attempting to live his shoestring-budgeted youth well, or at least to the best degree he is able to afford.

Having left Brooklyn for Moscow with the thought that his grandmother might provide a font of generational wisdom in support of a stunning academic study, instead Andryush finds an endearing but ailing matriarch, prone to fits of forgetfulness yet stubbornly set in her ways; the dynamic, at times, recalls Kenneth Lonergan’s by turns comic and heartbreaking play The Waverly Gallery, also about a young man’s relationship to a fading family matriarch. With the sly, between-the-lines humor characteristic of his work—notably his nonfiction articles for The New Yorker—Gessen provides a mix of sociological observation and clever particulars: the ins-and-outs of text-messaging in Russia, where “))))” communicates laughter, the number of half-parentheses relaying the degree of intended levity; the earthy particulars of Russian cussing; and at least one extended set-piece featuring untrained Andryush’s wrestling match with perverse Soviet-era plumbing.

This is a novel of traditionally Russian bulk (Tolstoy, Dostoevsky), and one that really works hard to situate a reader in the material world. It is a novel that will teach things about a particular time and place if the reader cares to learn. (The reader may not care to learn, but then, you know, that’s too bad, Reader.) Resonating with the name of Andryush’s go-to work-space The Coffee Grind, A Terrible Country, apparently by choice, is nothing if not expressive of a grind; the grind, in part, appears to be Gessen’s elected subject. Seeing through it is what a body must do to believe another world is possible. Or is that just the grind driving us toward a delusional state?

“I wasn’t sure,” says Andryush of Yulia, his eventual refuge from the coffee-shop where he goes to escape his grandmother, “I could handle being in the constant presence of someone so morally acute.” Growing close to the Russian native, he learns to see the country itself through her eyes: “Walking around with Yulia clued me in to the great utopian experiment that had been attempted here, on the level of the buildings themselves, before it was abandoned and forgotten.” And in this way, A Terrible Country, a big book, like those of yore—nineteenth century tomes hefty with sociological breadth and reams of precisely observed behavior—might be said to be very much about the sort of hold that kind of big novel had on a reader; Baba Seva, whom Andryush treats tenderly yet has, for most of his life, ignored, is a vessel of antiquated views and behaviors, increasingly forgetful and prone to being forgotten. It’s a state of being with which the tomes of yesteryear could relate, if only they had any awareness without our minding them.

When present, Dima, the entrepreneur older brother, is always rushing from rooms with impatience, denying his grandmother even one game of anagrams.

Andryush, and A Terrible Country itself, are patient enough with her for anagrams, and also to ask what it is that she might know that our narrator does not. And by the end, anyhow, our innocent abroad is no longer quite so innocent. Yet the story that he narrates—through the daily grind—shows how well he remembers when he was.

“I Welcome the Extreme Pathos”

“The touch of History is unmistakable. It starts as a cold scrotal grip, alarming and, at the same time, strangely pleasant. History cannot be confused with any other sensation, it travels up the urethra and pelvis, an armada of pinpricks, thousands of them, decidedly foreign but not unwelcome; all whispering, “You are part of something larger.” – Our unnamed narrator, an inmate in Duchess County, New York

“I was beginning to wonder,” observes Andryush somewhat late in the novel he narrates, “if I had promised more to the people around me than I could deliver. If I had made myself out to be a better person than I could be. I couldn’t shake the occasional feeling that I was in over my head.”

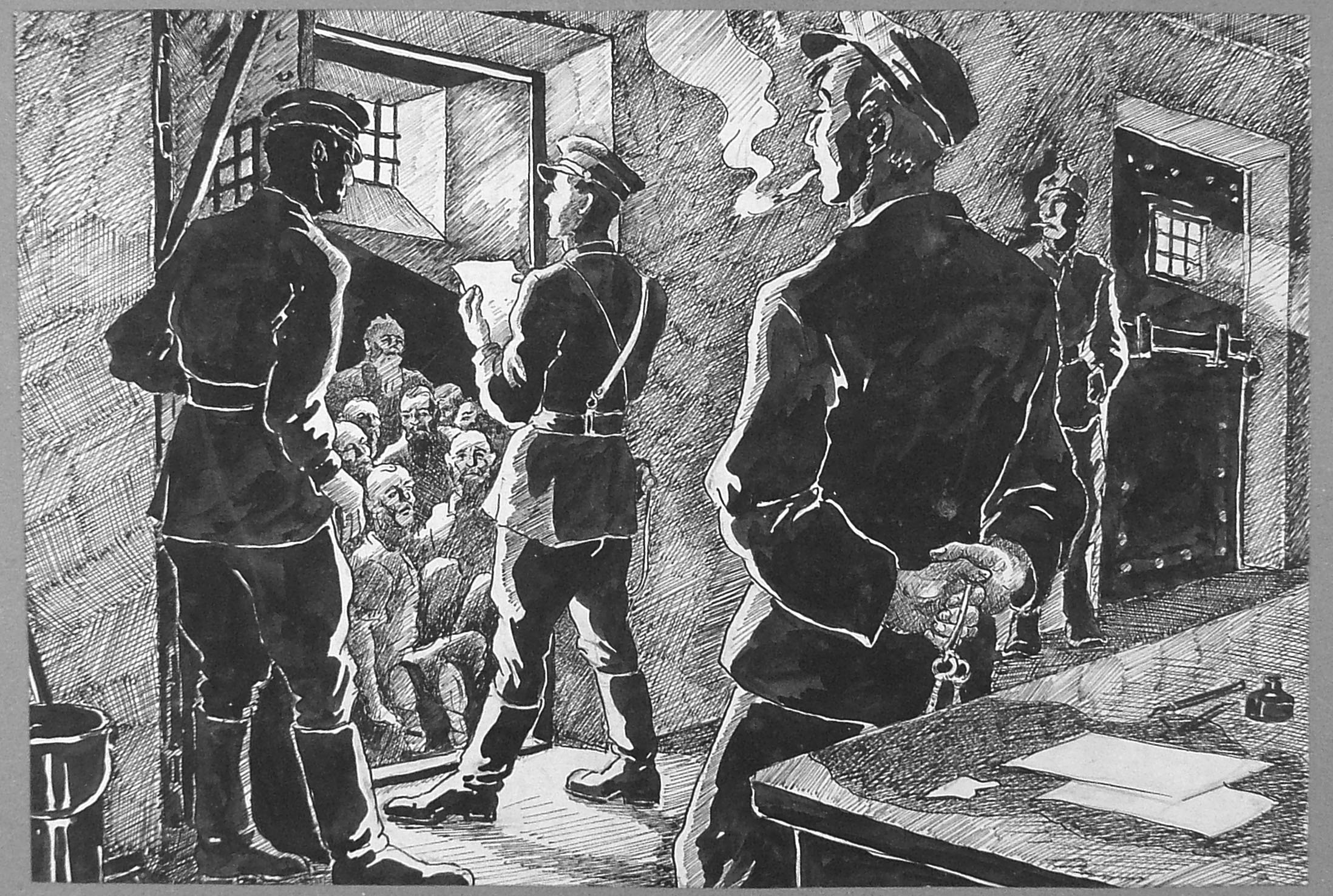

Like Andryush, the unnamed Sri Lankan-born narrator of Ryan Chapman’s debut novel, Riots I Have Known, is definitely in over his head. Yet he entertains little doubt about that fact, and perversely seems almost to enjoy it: “The Holding Pen is worth a riot, worth a hundred riots. This work will outlive us all, it will outlive us all and gather momentum and be taught to schoolchildren and recited at the commencement of major sports events.” The Holding Pen is the cheeky title of the wildly successful prison literary journal (dark comedy, remember) at whose editorial helm our narrator teeters. Riots I Have Known as a whole is not so much a narrative progression of any kind, as an unraveling of its protagonist’s attempts to get verbally on top of a sequence of events by which he is decidedly—and terminally—overmatched.

He will die, and not, like, in some far-off literary gloaming with a single tear falling beneath the rising of a crescent moon; the narrator of Riots I Have Known will cease to draw breath soon after his fellow inmates breach the barricaded doors of the Will and Edith Rosenberg Media Center for Journalistic Excellence in the Penal Arts. The pages of the novel comprise his elegy to himself, or the foreword to his final issue as editor-in-chief of The Holding Pen; less grandly, Chapman’s pages contain (all 119 of them) every thought the narrator thinks to “auto-publish,” the conceit being that it’s in essence a live blog, and an account of how it was that the “post-penal literary magazine” he edits came to incite such a riotous response.

Chapman’s narrative approach is funny-smart on several levels, a few of which go as follows:

It’s funny as a send-up of sophomoric writing, the sort breathless with the conviction that the next word committed to the page will be the author’s last—even as, structurally, it shares many of the same qualities as said writing.

It’s funny in flashes as an inspired cultural spoof, akin to, say, Mad Magazine: “Last December a restaurant named Napkins opened in the Mission District of San Francisco, the newest addition to celebrity chef Frankie DiCredenza’s growing empire… his plywood tables had been pulled from the refuse pile at a nearby wharf and gave the judges several splinters in their hindquarters…”

It’s funny as to the place of “literature” in today’s cultural arena, where individual titles appear to live and die in an all-but-instantaneous slipstream of engagement (like-clicks or hate-clicks or need-to-know-clicks or you’re-the-me-I-always-wished-I-could-be-clicks). ‘Everything is Marketing’ read the words of the prophets written on the subway walls. Except those words weren’t written by any prophet! Rather they were spoken through serious nicotine withdrawal to the ‘Voice Type’ feature on GoogleDocs by a freelance copywriter wanting only for a stable source of income and a 401K!

Anyhow, or regardless, the more Chapman’s narrator insists that the viral response to his live-blogging must assure his immortality (“I see my outpouring of feeling has engendered the same in many of you, judging by the upvotes in Reddit’s r/mcnairyfanfic. I thank all of you for your support, your enthusiasm, and your—how to put it?—imagination.”), the more apparent it feels to the reader that as soon as the day’s events are done, nobody will recall more than a few words of the proceedings, if even that.

Yes, there are various gestures at plot, but gestures whose intent Chapman’s self-infatuated narrator undercuts with his digressions and fluttering attention to whatever’s currently of the moment: “I see activity’s picked up on #westbrookriot. I apologize to my many fans that I cannot address all of your queries. Would that I had the time!”

There’s our narrator’s up-by-his-own-bootstraps story, from obscurity to being the favorite of “the Hilton Hotels advance man” to his immigration to the U.S.A.; there’s his time as “3 West Seventy-Second Street’s consummate doorman, the custodian and sentry for a storied address built with Carnegie money in 1928, rehabbed by Halston in 1976, and managed by a Saudi-based holdings company since 2009”—an epoch that culminates, or craters, with the murder of several well-to-do widows and our narrator’s never-quite-admitted-to-the-reader culpability; then, in prison, his leadership of the literary journal under the politically calculating Warden Gertjens; the outright menace of the likes of O’Bastardface and Diosito; a betrayal by a journalist named Betsy Pankhurst and a furtive romance with a fellow inmate who belongs to no one group but passes along the periphery of many (McNairy). There are the screws, meaning the guards, and screws, meaning what our narrator and McNairy consent to do with a donut.

Maybe you will ask, though: Is the United States penal system really a subject fit for laughs? Riots I Have Known steps delicately around that question, its rendering of life on the inside just credible enough, with just enough pathos, for the reader not to feel as if the setting is solely an occasion for the author’s jakery: “Those first months are the hardest, don’t let anyone fool you, your body and your mind refuse to adjust to the rhythms and limitations of prison life: first your bowels will not cooperate, then they cannot be stopped. You’ll write letters to everyone you’ve ever met, then you’ll have nothing to say.” The satire of a benighted literary existence is without a doubt heightened for being situated in a literal, as opposed to figurative, prison. (By way of parallel, Andryush, Gessen’s prisoner of “the grind,” concludes A Terrible Country by taking a job as the Inaugural Chair of Gulag Studies.)

To further the comparison between the two texts, certain thematic valences notwithstanding, Chapman’s debut is an all but negative image of Gessen’s sophomore effort—discursive where Gessen’s narrative is straight ahead; knowing and bawdy and essentially unconcerned with portraying human relationships at any great length, while that effort forms the pith of A Terrible Country; over-brimming with uprooted wit whereas Andryush walks, block by block, to discover where he might truly belong. That question is vain, if not quite moot, in Riots I Have Known. Every one of his readers knows where the narrator comes from, a fact he will share again and again in a drowning grasp at meaning. All that truly matters for him, in the end, is what’s bound to happen next. And how the internet feels about it.

Chief among the qualities of Riots I Have Known is its brevity: ‘you can read it in one sitting’ seems to be our moment’s preferred form of backhanded praise. Meanwhile, the literary journal the narrator ostensibly dies to introduce is what reader and narrator both will never reach. This is also funny, and perhaps emblematic of an age in which most people, apparently, would rather hear themselves carry on than apprehend what the hell anyone else might mean.

Chapman (a former Brooklynite) even has some fun at Gessen’s expense, or at least the expense of some semblance of the Brooklyn-based publication he co-founded, characterizing a fictive n+1 (“###”) as:

an upstart literary magazine from Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Of course, I now know the publication quite well: they graciously send me the quarterly and its various sister projects. I gather it’s an intimate operation, a clubhouse of logorrheic Harvard grads and rotating piles of interns. Kudos to them and their dedication to the written word! In these trying times I can think of no goal higher than the self-imposed edicts by these fun-size Sontags to reshape the worldview of each and every Brooklyn millennial.

Chapman’s doomed narrator is past all reaching; no words to the contrary can affect his opinions. Yet maybe someone ought to have told him, given how socialism is polling among millennials now versus when n+1 began, that the fun-size Sontags might be onto something.

J.T. Price is the Managing Editor of Epiphany a Literary Journal. Find him on Twitter (he, too, dislikes it) or www.jt-price.com.