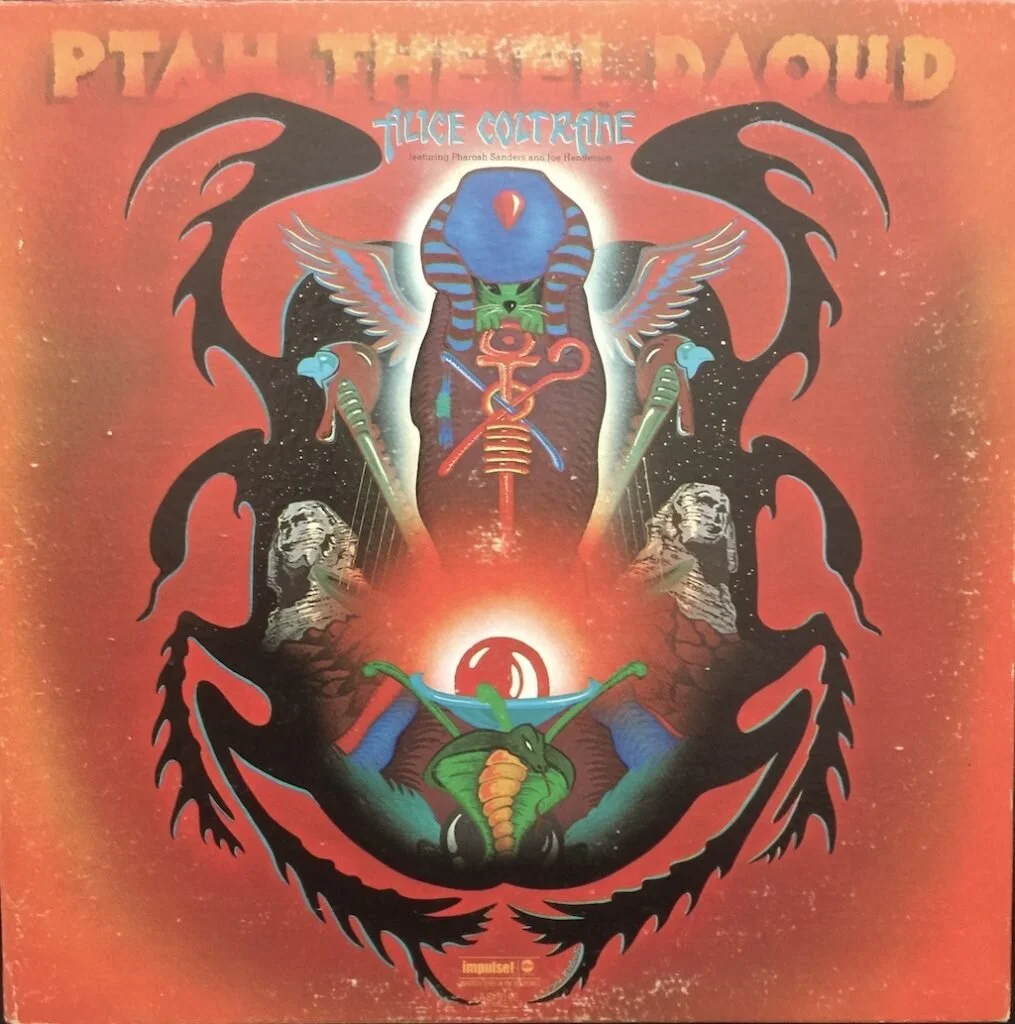

Music for Desks: Shakirah Peterson on Ptah, the El Daoud

have you ever seen alice coltrane play the harp? the organ? the piano? it’s hypnotic. her fingers glide like they’re made of silk and suede, velvet and velour.

alice didn’t play instruments. she poured them.

every apparatus she touched became an extension of her essence. her music has an aura that lulls unlike anything else. it keeps me coming back day after day, page after page, sentence after sentence.

in the late 1970s, alice adopted her sanskrit name “turiyasangitananda.” it translates to “transcendental lord’s highest song of bliss.” bliss emits bliss: i glide my fingers across my own instruments (a macbook keyboard, a felt tip pen on weighted paper). i attempt to channel what alice pours into me onto the page.

she composed her third album, “ptah the el daoud,” in the basement of her home in 1970, three years after her husband john coltrane died of liver cancer. the removal of his spirit from the physical realm had sent her into metaphysical turmoil. her heartbeat would shift to the right side of her body. the hair on her head would stand on end as if electrically charged. in the liner notes of the album alice wrote, “my meaning here was to express and bring out a feeling of purification. sometimes on earth, we don’t have to wait for death to go through a sort of purging . . . that march you hear is a march on to purgatory.”

it is the second song on the album, “turiya & ramakrishna,” that leaves me purged and pure.

the song opens with a piano melody that has become so familiar to me i can taste it, delectable and warm. the bass that enters alongside it soothes my ears. only god can pull me away. these sensations are a product of a blues pentatonic scale, one of the oldest known music scales in the world. archaeologists once dug up ancient flutes carved out of bird bones from more than 40,000 years ago; many of them were tuned to the pentatonic scale. it’s an ancestral feeling, a tune i know from another time. it unravels me.

i am transported to a world of unwinding. i become confident in my ideas and talent, comfortable in my art and voice. alice grants permission for vulnerability to reign and i start to feel at home. i choose words like flesh over skin, lull over calm. she makes me drop the capitalization at the starts of my sentences, italicize my emphases; makes me feel soft and write softly – and that’s just in the first minute.

on the journey to minute two, bells begin to tremble. the drum is gently tapped, possibly the cymbals, too. together, they form a tambourine-like sound. it’s real quiet at first, but soon rises to the same frequency as the piano and bass.

a blend so beautiful it makes me want to combine my own sovereign sounds. i start blending prose with fiction, poetry with magical realism, narrative with ancient archives. i write in every genre, expressing myself across multiple mediums. for both alice and me, one mode of expression is not enough.

periodically, the instruments rise to a single frequency: at minute three, at minute six, then again toward the very end. a sort of refrain, each lasting about thirty seconds. the refrain reminds me of church. in (black) gospel, the refrain brings us closer to god. through repetition, we create a call and response. we beckon the spirit to move us. we want to be heard and felt in heaven – the other realm, where salvation and glory live.

the alternation between the composition’s smooth, slow interstices and its charged refrain mirrors my own sporadic writing pattern. i often go days without writing a single word. this hiatus is never by choice. sometimes the words are there for me and sometimes they aren’t. when my hiatus ends, i can write thousands of words in one sitting. alice teaches me to love this in-between, to love the flux. each of my states is as important as the other, and together they constitute a whole.

at the end of the composition, alice modulates from d-flat up to d and back to d-flat before going out. she lends this structure to king pleasure’s “parkers mood,” the part where the lyrics say, “come with me.” “it’s like god asking us if we want to go home,” she writes in the liner notes. “that kind of feeling”.

my writing is continuous, just as the ending of “turiya & ramakrishna” is much like its beginning.

•

“ptah, the el daoud” is named for an egyptian creator god. it translates to “ptah, the beloved.”

according to the memphite theology, a document dating back to 4000 b.c., ptah existed before all things and created humans through the power of his heart and speech. he was known as the god of craftsmen. his following, the high priests of ptah, were sought after by the pharaoh for royal projects, filling in the roles of chief architects or master craftsmen, the people responsible for the design and decoration of royal funerary events. in thebes, the oratory of “ptah who listens to prayers” was built in the village where workers and craftsmen lived. in memphis, large ears were carved on the walls of the enclosure that protects the sanctuary of the god.

alice composed “ptah, the el daoud” with the same devotion as those worshipers. in her basement she brought together brass and string, metal and wood, to build her own temple of expression. she blends ancient egyptian mythology with hindu philosophy to make sense of her world.

these days, i fathom my world on a l-shaped desk in southern louisiana. my apartment is located on the unceded land of the chahta yakni peoples, 50 miles away from where Nelson Peterson married Sarah Philips in 1886 – my earliest known ancestors. here is where i isolate from society, but am never alone.

when i am seated facing north, i face a large window. on display: a dozen bald cypress trees, finally sprouting new leaves. pinned across the wall to my left: photos of my mother in her twenties, my late grandmother, affirmations from myself and mentors, a 1900s family portrait of my maternal lineage. all reminders of where i’ve come from; spurs to be appreciative of who/where i presently am.

to cleanse and comfort, a glass of fresh lavender stems sits next to a bundle of white sage. for warmth, i adjust the color of my mood lamp to a blend of yellow and orange – in replication of a sun. “ptah, the el daoud” plays on a record player behind me, a gift. when i light the sage, its smoke floats through the open window. i skip to song ‘02’ and press repeat.

now that my temple is prepared, i enter the holy space of “turiya & ramakrishna” and am transported to an otherwordly plane.

my writing often speaks to and of the other. i use speculative fiction, essay, and poetry as outlets to other worlds, other lives, other realms, other possibilities. i’m concerned with what happens beyond and before, around and outside of human existence. writing to alice’s composition is a way of pushing myself toward that fullest of expressions.

in my attempts to express realities i envision but cannot see, the english language/ideologies often fail me. alice shows me how to pull from other schools of thought, to allow philosophies outside of my own to inform my art, to look beyond my own existence/experiences to make sense of the present.

—

shakirah peterson is a mfa candidate in creative writing at louisiana state university, where she serves as the editorial assistant at the southern review. born and raised in south central los angeles, she now breathes in baton rouge with her cat, fable.