What We're Reading Now: Dian Parker on The Effulgent Jean Giono

“It was an extraordinary night . . . the sky was vibrating like sheets of metal…. It was simply that the sky came down and touched the earth, raked the plains, struck the mountains, and made the corridors ring.” These are the first lines of a book that has cast a lifelong spell on me.

I’d been living in cities ever since graduating from high school. A city is controlled by time. Most days in New York, London, and Seattle, my home for twenty years, I’d been unaware of the sky except to take note of the temperature for how to dress. Time has been swift and precise, filled with appointments and getting ahead. Time has controlled me. Until one day, while visiting a friend in the country, who suggested a book that might offer a bit of respite to my hectic life.

The novel, Joy of Man’s Desiring by Jean Giono, is the story of twenty peasants living and working their farms on the Grémone Plateau. Their fields are vast and they live far apart, yet they travel for miles to help one another sow and harvest the wheat, hunt deer, tend the sick, and bury the dead. Life is filled with backbreaking work. One night a man appears, having walked a long way, and finds the farmer Jourdan plowing his field with his old horse. Jourdan and the man smoke a pipe together. The man asks Jourdan what he thinks of the night. Jourdan says,

“I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“Nor have I,” said the man. “Orion looks like Queen Anne’s lace.”

“What did you say?” asked Jourdan.

“Orion is twice as big as usual. There he is, up there. Stop. Up there. There. Do you see?

“No.”

“I have never been able to show people things,” said the man. “It’s curious. I have always been reproached for it. They say: No one sees what you mean.”

“Who says that?”

“Oh, someone.”

“A fool,” said Jourdan.

“But,” said the man, “you haven’t seen Orion, either.”

“No,” said Jourdan, “but I see the Queen Anne’s lace.”

“That’s a pure heart,” said the man, “and a good will.”

From that point on, the man, called Bobi, lives and works with Jourdan and his wife Marthe. The couple’s life changes, as does everyone’s on the plateau. Bobi awakens in the peasants a deeper, more profound, alive world than they had ever imagined. After Bobi suggests they give their extra bushel of wheat to the birds rather than sell it at market, their winter world is transformed by thousands of colorful, singing birds, and they spend weeks watching the sky fill with bright blue and gold, yellow and red. “Each time that the whole band scattered around the pile of grain, inside Marthe a feather flower burst into bloom, but it had wings of wind, of plains, and of mountains, eyes of sunshine, a blue breast of evening in the country, and a rustle of all the meadow insects.”

Throughout the book, Giono’s rapturous nature descriptions filled me, tugging at me to rethink my choices, asking me to go deeper inside myself, searching for what nourished me. Cities certainly didn’t, but in my business where else could I go for the professional life I sought? I was depleted, too much in the world, and still so young. Bobi tells the couple, “Youth is neither strength, nor a supple body, nor even youth as you conceive if it. Rather, youth is the passion for the impractical, the useless. . . . The less one thinks about money, the better it will be.”

As I sat drenching myself in Giono’s world, it was as if I knew I had a soul. When Bobi suggests Marthe and Jourdan plant narcissus bulbs in their field that could yield five loads of oats, my soul flung out wings:

The night was velvety and liquid. It lapped gently against the cheeks like cloth, then it receded with a sigh and could be heard swaying in the trees. Stars filled the sky. They were no longer the stars of winter, separate, brilliant. They were fish spawn. There was no longer any form in the world, not even of adolescent things. Nothing but milk: milky buds, milky seeds in the earth, the sowing of creatures, and star milk in the sky.

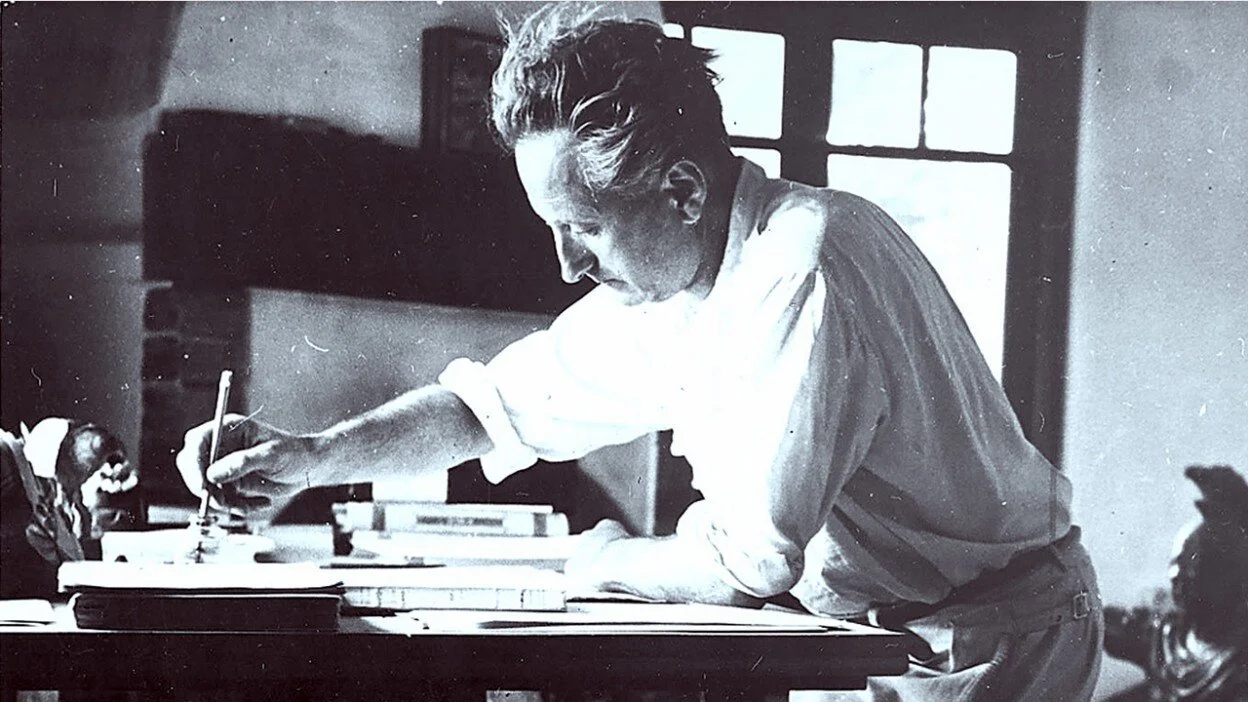

Jean Giono was born in Provence in 1895 and died in the village where he was born in 1970. He dropped out of school at 16 to support his family and fought in WWI at the brutal Battle of Verdun, where his eyelids were burned with mustard gas. When the war ended he began to write. He was an outspoken pacifist and in 1939, when he was 44, he was arrested by the French government for opposing the war publicly and spent time in jail. Giono wrote novels, poetry, drama, literary criticism, historical narratives − over 50 books, most of which are not translated into English.

Henry Miller said of Jean Giono, “The most inanimate objects yield their mysterious vibrations. The philosophy behind this symphonic production has no name: its function is to liberate, to keep open the sluices of the soul, to encourage speculation, adventure and passionate worship.”

Giono is fearless in giving voice to the natural world. He speaks the season’s courses and charms. The animal’s romps, delights and appetites. The water’s roil and languor. The flower’s thirst, the marsh’s suck, the tree’s blood. Humming constellations and moaning houses. Giono pressed me to open my senses and to listen to everything — deeply, and with love.

“There are builders of invisible things who do not bother with houses, but who construct vast countries better than those of this world.” Giono is that epic writer, with no fear of being too big. He writes about the unruly, the untamable, the wild, the unceasing, the alive. When the peasants gather for their annual feast, everyone gets drunk on the wine from the grapes they’ve grown. “To be guided by one’s blood, let one’s self be beaten, explored, let one’s self be carried away by the galloping of one’s blood to the infinite prairie of the heavens smooth as sand . . . all these calls of the blood would be calls of joy.”

Joy of Man’s Desiring by Jean Giono so rocked my world that ever since my first reading, I have devoted myself to a life more tuned in to the seasons and to writing. I eventually moved to Vermont, surrounded by forest and birdsong, and write in gratitude to the natural world. And to Jean Giono who was unafraid to express in euphoric language the sheer majesty of nature in its all-embracing power and terror and glory. His book awakened me. To this day, and after multiple rereads, I am still in awe and wonder at the genius and power of this book. He delivers a blow every time.

—

Dian Parker’s essays and short stories have been published in The Rupture, Critical Read, Anomaly, Upstreet, 3 AM Magazine, Bookends Review, Deep Wild, among others. Her work has been nominated for several Pushcart Awards, and awarded an Artist Development Grant from the Vermont Arts Council.