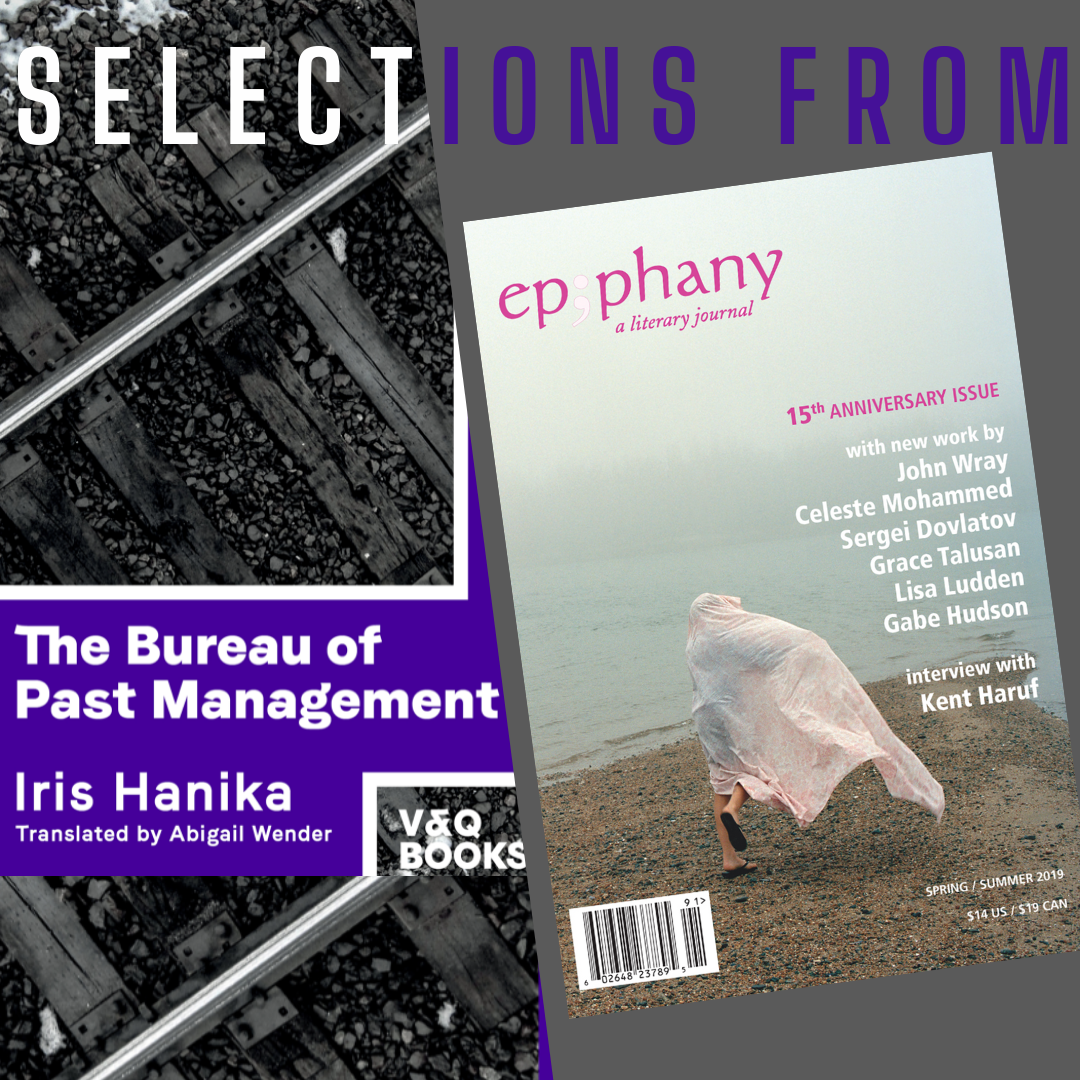

"Graziela," from Iris Hanika's THE BUREAU OF PAST MANAGEMENT, translated by Abigail Wender

Editors’ Note

Each of us has something that feels essential to who we are. For Hans Frambach, it's the crimes of the Nazi era, which have hurt him for as long as he can remember. That's why he became an archivist at the Bureau of Past Management; now, though he's wondering if he should make a change. For his best friend, Graziela, that past was also her focal point — until she met a man who desired her. From then on, sexual pleasure became the key to her life. In this excerpt, Hans considers the value of his friendship with Graziela, the only friend he has.

The Bureau of Past Management was recently selected by the Financial Times as a Best Book of 2021. In a review in the Irish Times (September 2021), Catherine Taylor wrote, "This December marks the 20th anniversary of the sudden death of the German writer WG Sebald. Much of Sebald's greatest work was a examination of the guilt of Germany's Nazi era as experienced by subsequent generations, a theme echoed by Iris Hanika in her bold and absorbing novel, which won the European Prize for Literature and is now translated sensitively by Abigail Wender."

We’re proud to say that Epiphany published this excerpt from The Bureau of Past Management, under the title “Graziela,” in our 15th Anniversary Issue. Congratulations to Iris and Abigail on the publication of their excellent book. And now . . . on with the show.

—

Graziela looked like Picasso had painted her, like one of Picasso’s portraits of Dora Maar. Except it wasn’t artifice; she was larger than art, larger than nature. She just looked like art.

She had big eyes, a big nose, and a big mouth, and the single elements of her face were arranged as if they weren’t connected to each other in any reasonable proportion so you couldn’t really form an opinion of them.

The nose was a little skewed. From its point of view, it slanted to the right, from the onlooker’s, to the left.

Somewhere under her forehead, her eyes drooped. They were gray-blue.

Her big mouth had almost no color; you only noticed it when she spoke, rather like an unusually textured shape moving around an opening in her face. When she didn’t speak, her mouth was lost in the rough sketch that served as her countenance.

When they’d first met, Hans had thought a lot about Graziela’s face and couldn’t decide whether she was very ugly or strikingly beautiful. He stared at her unabashedly whenever they were together, and she stared unabashedly back, all the while describing the various aspects of her personal suffering that had stemmed from the Nazi past.

At the Berlin symphony (Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 C-major, Op. 21, and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 A-major, Op. 92, edition Jonathan Del Mar), he’d seen her face made-up for the first time (she’d met Joachim by then). She’d bathed her lips in blood, bolted down her eyes with kohl and heavy mascara, and made her face into an Expressionist painting, which you really couldn’t enter because in the middle of it her big nose pointed you in the wrong direction.

How could anyone walk around in the world looking like that!

Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to divide the letters of her first name by three. He tried it automatically every time she popped into his mind, but he failed, of course; her name could only be divided perfectly by three by combining it with Schönbluhm, her last name, which was somewhat reassuring. However, he couldn’t constantly think of her by her whole name as if hers were the name of some Nazi SS-Major. To him, she was Graziela, unfortunately eight letters, and eight was not divisible by three, and there was nothing to do about that. The rule of three worked for Graziela only by combining her name with something that genuinely belonged to her, which then could be divided by three. “Eyes,” “nose,” “lips” didn’t work. “Cheeks” worked. “Grazielascheeks” made him happy because it was fifteen letters, his favorite number of letters, and when he divided them by three he got five. That was orderly, it worked, and could be no other way: fifteen divided by three equals five, five times three equals fifteen—an ace in the hole.

People were problematic for him, and people whose names couldn’t be divided by three were his first hurdle. (Clearly the office assistant, Frau Kermer, whose first name was Elisabeth, and whom he would never call by her first name, was an exception. Maybe this was why he never called her anything but “Frau Kermer”; that extra letter was the measure by which she would forever lack his affection.)

A face like Graziela’s was beyond simple aesthetic appreciation. Actually, when you look at someone over a long period of time, even if you don’t know the person well, she doesn’t look ugly. But also not beautiful. Ugly and beautiful stop being meaningful distinctions. Hans decided to find her face as beautiful as her body, which made him think less of Picasso and more of Botero, for it was firm and round and large like everything about her; her breasts were just extra knobs in the fleshy body she walked around with daily.

And it would have been so comfortable to live in Graziela’s magnificent body. There was so much room for every possible state of mind to collapse onto its soft cushions and not be hurt, but for Graziela, who theoretically had exclusive possession of her body, it was the total opposite. She didn’t observe herself with the eye of a connoisseur; instead, she thought her face was ugly and her body simply fat. She was like the old Federal Republic of Germany.

Lucky for her, she won the lottery—or so she thought when someone became interested in her body—and his name was Joachim. He wasn’t merely into her body as much as he was thrilled by it (he really was), and aroused whenever he thought about it. Her body excited the most extreme hunger in him accompanied by a certainty that his appetite would be quickly, happily satisfied. Repeatedly he said to Graziela, owner and occupant of this body, how incredibly much he liked it, and because Graziela had never known anyone who’d expressed any particular joy over her body, she immediately placed it at his disposal—meaning, she allowed him unlimited use without hesitation—and since then had begun to feel friendlier toward her outward appearance.

Because Joachim desired her body, Graziela looked in the mirror and didn’t think about dieting and tried to imagine what he saw. To be honest, she still failed to see how her body was beautiful, although he told her blatantly that it was, but at last she was content. After all, without it, she wouldn’t have a lover. She no longer judged her face by contemporary aesthetic norms; instead she focused on making herself more attractive, always making up her face and grooming herself with utmost care to keep her body ready for use. She washed often and used expensive cream on her skin, shaved her legs also in winter, went regularly to a hair salon, in good conscience ate chocolate but also more vegetables than before, and drank many liters of water so that the substance of her body would stay as healthy and fresh as possible. Now that someone coveted her body, it had become important. Graziela believed that their affair, hers and Joachim’s, had been rendered down to a pure kernel, to the essential thing. Moreover, she believed that this total reduction would bring the greatest fulfillment.

The whole point was to be flesh, nothing else. Her love would consist of nothing more, would have no feature other than sex, none of the other elements that made each person unique; love could be distinguished only by her gender, a common characteristic, and only through its most obvious feature; all others were deemed irrelevant. To be a woman and nothing else. To sing with Carole King or, better yet, with Aretha Franklin:

You make me feel

You make me feel

You make me feel like a na-tu-ral woman,

one of the silliest pop songs ever.

The whole point of love was to be stripped down to this one special element, which in reality was nothing special. Something special was only the stripping down.

Although Hans wasn’t aware of all of this, he’d seen how she had behaved and changed ever since Joachim stepped into her life. It hadn’t been lost on him—the way she now groomed herself, dressed elegantly, always with fresh-washed hair, always smelling of perfume and talking about “relation- ship issues,” instead of Auschwitz. Back in the day when Graziela wore jeans and sweatshirts and talked about Auschwitz with him, he’d thought she understood his misery because she shared it. That’s how they’d become friends. About her own misery, her own specific unhappiness, they’d never spoken—it had been, yes, it was completely neglected in light of the immense, vast misfortune they constantly talked about. That was before she switched sides and believed herself to be happy because she nurtured a so- called relationship.

He’d met this Joachim—the letters of whose name not only could not be divided by three but also added up to the most unpleasant sum—a few times only in passing when he arrived exactly as Joachim was leaving. Graziela always looked velvety, as if she’d been softened up, and Joachim positively sunny, which made Hans want to vomit. So he avoided meeting Joachim whenever possible. Once he ran into him just as Hans was saying goodbye to Graziela and came away from their meeting feeling somehow insulted. Now if he and Graziela arranged to meet at her place, he always made sure to ask whether or not she’d be seeing Joachim before or after, and if so, he arrived either late or left early, or suggested right away that they meet another day.

***

He took his coffee mug from his office cabinet where it was stowed every evening after he washed it, and closed the door behind him when he went to the kitchen where Frau Kermer’s coffee-machine brewed bitter coffee. All the office doors were open and the rooms empty. The graduate student was in the library, there were no interns around at the moment, and the boss, Herr Marschner, would surely not arrive until eleven. It was very peaceful in the archives where he worked at the Bureau of Past Management. Only the door to the computer room at the end of the corridor was closed.

The computer room was The Essential to the Bureau’s archive, an inter- connected meta-archive, and the computer room created central access to the various archives and documents that were needed for the management of the past. The Bureau’s archive was tiny and held only newly found material, unexpected discoveries, curiosities. Hans Frambach’s daily tasks were actually only a memory of archival science, an embellishment that one wouldn’t want to part with for nostalgic reasons—nostalgia itself a form of managing the past. He had no contact with the people who worked in the computer room. Anyway, they lived on another planet, were only to be glimpsed on their way to lunch, always together, and never spent time with anyone else. Without fail they materialized immediately if he had a problem with his computer, fixed it in two minutes at most, accepted his thanks with quiet contempt, and scurried back to their mainframe computer. He was, in effect, alone with Frau Kermer.

He poured the thick, pasteurized, sweet cream from the little bottle that sat on his desk into his coffee, and called Graziela, who was already on the phone before he’d heard the ring.

“Oh, Hans,” she said. “I’m so sorry, I have to cancel tonight.”

He pressed his lips hard together to create a facial expression, one that distinguished itself only a tiny bit from a smile. Then once again loosened his lips and said from the back of his throat, “Joachim.”

“Yes. Joachim suddenly has time tonight and I haven’t seen him in a week.”

“Yes,” he said, and thought of how he hadn’t seen Graziela in two weeks.

They were silent for a moment.

“Good. Or not good. Let’s talk later, I have to work now.”

“I’m very sorry.”

“It’s okay. Bye.” And he hung up.

On the outside he was cold and inside he was empty. He stared at the equally empty little windows on his monitor screen. There was a lump in his throat he didn’t want to swallow. He typed his password, an abbreviation of his own name, “hafram,” at the prompt in one window and then the Auschwitz SS Commander’s name, “hoess,” in the other. The Bureau’s archival program welcomed him, and he took the next sheet of paper from a box holding the bequest from Siegfried Wolkenkraut in order to feed it into the archive’s primary research.

***

ACCOUNT

OF

MY

STAY IN

VARIOUS

CONCENTRATION CAMPS

At the end of January 1943

I was

deported

from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In

Theresienstadt

I lived

with my parents

for one year.

My parents were not

deported

until October 1944 to

Auschwitz

and there

immediately

murdered

in the gas chamber.

I was

deemed fit for work

at the selection on arrival in

Auschwitz and therefore

was not

immediately

murdered

in the gas chamber.

In camp

I

survived

later

selections,

likewise

the death march

to evacuate

Auschwitz in

December 1944 that brought me to

Bergen-Belsen.

There

the British troops

freed us

in April 1945.

Today

I live

in Lower Saxony near Northeim in the village of Imbshausen.

I work

as a farmhand.

I am

a lithographer and poet.

***

The sheet of paper was not dated. It was already the forty-sixth sheet with this exact text written by Wolkenkraut. Frambach stamped it with the Bureau’s official stamp and wrote the archive number on the line provided. Then he typed the number in the table on the screen and wrote in the column “Title,” “Account of my stay in various concentration camps”; in the column “Style,” “Account”; in the column “Size,” “1 p. r.”; in the column “Description,” “good cond., typescript, n.d.”; and in the column “Comments,” “sharply broken lines.”

There were also handwritten versions of the account. The individual versions showed no variation of content whatsoever; there were only those without line breaks, some quasi-prose, and ones like this, with lines broken in a quasi-lyric form. Wolkenkraut had never dated these accounts so it was impossible to establish whether in time he would have broken the lines even more sharply or whether he would have found his way to a continuous text.

***

Wolkenkraut’s bequest had been missing for a long time. However, no one at the Bureau of Past Management lamented the missing estate because the few samples he’d produced in his short life were not promising nor had they caught anyone’s attention. Apart from a slim volume of verse published in 1951 (“with three illustrations by the author”), plus two short essays that appeared that same year in a Lower Saxon local paper, he’d had no publications and his lithography had been exhibited only once, in a long-gone gallery in Göttingen, as evidenced by a little catalog. In March 1953, Siegfried Wolkenkraut was run over by a tractor in Imbshausen near Northeim and died at the scene of the accident. He was twenty-nine years old, leaving behind a wife and daughter. What became of them had been no one’s concern until a wooden box with his bequest arrived at the Bureau. In all likelihood Wolkenkraut’s wife was no longer alive: otherwise she would have inherited the box; probably only the daughter, Mafalda, had remained—and she left no one behind in Schweinfurt when she jumped from her apartment’s balcony on the 12th floor. She had placed a note on the box requesting that it be transferred to the Bureau of Past Management. Nothing else. No further explanation, also no suicide note, according to the Probate Court’s notification letter.

***

He took the next paper, laid it down in front of him, read it, turned it over, read the back, turned it again, stamped it, gave it a number, and typed into the computer the title he’d copied from the preceding entry: “Account of my stay in various concentration camps, Account, 1p, moderate condition, handwritten, paper creased, n.d., verso: price list Merzenbach Co. (milk- ing pails, pitchforks), dat. 1.VII.1948, unbroken lines” and placed the sheet upside down on the left tab of the portfolio, where the first already lay.

The date of the price list on the back was a clue, but not a reliable one. How long would a price list such as this hang around a farm until it was no longer needed and thrown out? Wouldn’t a price list be valid for quite some time? How important were new milk pails and pitchforks? Surely there would have been a few of these already on hand. After the currency reform, hadn’t there been money to invest in things like that, or had there been something else more important?

***

I walk into evening and lie under night’s slaughtering axe.

No title (I walk into evening), Note, 1p, 1r, poor condition, handwritten, n.d.

***

Wherever Herr Marschner appeared there was an abrupt commotion in the office. His good mood whirled around like a carousel swing, and he was the pole in the middle. If he made a slight movement, the carousel made a larger one, so the empty swings flew on long chains in a wide circle around him, clanging against walls, doors, and cabinets, upsetting all the cups, and crash- ing into windowpanes. He was such a noisy person that Frambach could hear him at the entrance door from a distance of thirty feet, even though he sat at his desk behind the closed door. He heard Marschner trying to amuse Frau Kermer with the tale of his hunt for today’s parking spot, a long search ending in an escapade, and which seemed to work because Frau Kermer’s shrill laughter scissored again and again through the deep tones of Marschner’s monologue. Then came an almost peaceful moment, only a murmur, probably while Frau Kermer reported what had happened since yesterday afternoon, what was in the mail, and who had phoned. Then once more Marschner’s fairground-trumpet-and-clang, until Frau Kermer’s chainsaw laughter united with Marschner’s heavy steps, accompanying him for another moment.

Frambach heard Marschner rolling close and prepared for his boss’s appearance. In general he barely paused at Frambach’s door, but after a dry knock, he tore open the door to the cozy room, filling it to bursting with his brio and carousel-clang.

“Good morning!” shouted Marschner, and squeezed Frambach’s shoulder, “Is everything in order?”

“Of course, how else should it be.”

The computer worked, the coffee tasted terrible, Wolkenkraut wrote the same passage on and on.

“I’d like to speak with you,”

“yes, Frau Kermer already set up the appointment,”

“how would half past eleven be?”

“yes, I’ve reserved the time.” Frambach gave in,

Frambach gave back,

Frambach gave over to protocol

as Marschner studied his watch, shouted “Jeez! It’s late! I have to handle a couple of calls, but then, wow, I’ve got wonderful news for you!” Once more he squeezed him on the shoulder and stomped out, leaving the door ajar. Straight away Hans closed it again. “A couple of calls” meant at least a minimum of five. What it also meant was that their discussion would take place at noon at the earliest, more likely 12:30, and although Marschner was never punctual and although Hans knew this, and knew precisely the extent of Marschner’s chronic lateness, he let himself be disappointed, and was already feeling anxious shortly before 11:30 when Frau Kermer called, asking him to have patience. But he was restless, couldn’t concentrate, and stared constantly at the time.

***

He knew all of this but it was no use to him. At any moment of the day Hans could tell you precisely what mistakes he was making and how those mistakes grew from his unhappiness and how his unhappiness stuck to him and also grew worse; and, on the flip side, how his unhappiness grew from his mistakes and had become a habit that would continue for eternity—he knew this precisely, but it was still no use.

***

He called Graziela. After greeting her, he explained that a meeting with Marschner had been arranged for 11:30 but had been delayed, as she must have quickly perceived since he was phoning her now, at 11:37; besides that, he guessed the meeting wouldn’t take place until 12:30 so he had more than enough time to talk now and asked her, so how are things?

Naturally this question was redundant, things couldn’t be other than out- standing owing to her upcoming date with Joachim—her whole life circled around that man—who, it appeared, had less command over his free time than he would have liked due to his obligations as a husband and family man. If Hans had ever considered an amorous relationship with Graziela for any reason (e. g. love) because it would have been practical, and if their relationship had not been atom-bomb proof, and if from the start they had not been like siblings, he would have been jealous (which he was) and not just frequently irritated, and surely would have ended their friendship long ago. But Joachim had never been a danger. Quite the contrary. In fact, there’d been a lot more to talk about since Joachim’s appearance. Instead of discussing how their families and nationality had entangled them in Germany’s terrible history, they now analyzed and evaluated Joachim’s every comment and how best to smooth away his trivial irritations. The need was always urgent and existential, and Hans had asked himself more than twice if he really wanted to play the role she’d cast him in. He was as good as buried in the role, as walled in as he’d be in the concrete walls of an anti-aircraft bunker. When she shared with him the fruit of her reading—a woman’s magazine—it became clear to him that the status of any extramarital affair, statistically speaking, remains the same unless the adulterer separates from his marriage partner within the first year of the affair. And Graziela had nurtured her bond to, relationship with, dependence on Joachim for roughly four years.

At the same time, she’d let Hans know that he’d become even more important to her since she’d met Joachim, though that didn’t seem possible.

She began reading The Coup de Grace by Marguerite Yourcenar (1939, tr. by Grace Frick), and after the first three pages informed him that the book was not a joy but a total slog. On page 14 of her edition she found the sentence:

Friendship affords certitude above all, and that is what distinguishes it from love.

She quoted this to him promptly, adding that the book had already given her so much she needn’t finish it. Once again she repeated the sentence, remarking that it was worth the whole thing.

At that he’d almost wept. (Thank you, Marguerite Yourcenar!)

He’d gone out right away to get a copy to read again because he couldn’t recall the passage. He didn’t tell Graziela—that would have been obnoxious, he thought. This time he read the book in the original, and not only to the sentence:

L’amitie est avant tout certitude, c’est ce que la distingue de l’amour,

but to the very end to pay his debt of gratitude to Marguerite Yourcenar, although he found the story unpleasant. What fascinated the French about Baltic nobility, German military, and war in East Prussia, he’d never understand—he simply noted it was so. These days he thought differently about Germany, that is to say, much less frequently than he had in the past. But he was disturbed that this woman-hating book was written by a woman.

“Everything’s fine,” said Graziela, just as he’d expected, “and you?”

“The usual misery,” he answered.

“Well, then, everything’s all right.”

—

Iris Hanika has been honored with numerous awards, including the Rome Prize, for her books and novels. The Essential (Das Eigentliche), published in 2012, was awarded the European Union Prize for Literature, the Prize of the Litera-Tour Nord, and was shortlisted for the Wilhelm-Raab Prize. It has been translated into 11 languages.

Abigail Wender’s translations and poems have been published in Asymptote, The Cortland Review, Disquieting Muses Quarterly, Kenyon Review Online, Tupelo Quarterly, and other journals and anthologies. This selection from The Essential was a finalist in Epiphany’s translation contest.