"Restitution, Or, A Lonely Walk Through The British Museum" by Frances Nguyen

“They just come in and take all the souvenir,” my father said, holding out his phone at arm’s length to take photos.

He was visiting me in London, where I moved after college in 2011. I’d brought him to one of my favorite places in my new home—the British Museum.

I was first introduced to it through the film “The Mummy Returns,” in 2001. I loved the character Evie (played by Rachel Weisz), a treasure-hunting librarian who went on apocalyptic adventures in Egypt. More than that, she was the guardian of old things, things that held memory.

The film franchise, while admittedly a white savior fantasy thrice recycled, first sparked my interest in the ancient Near East, which I studied in school—much to my father’s heartbreak, I abandoned a trajectory toward diplomacy, the dream that I’d promised him. Taking him to the museum was both a way to explain and apologize for graduating with as confounding and unemployable a degree as ancient history.

It was the beginning of a new tradition: I spent my college years and the decade that followed searching for a place to call my own, and when- ever I landed somewhere new, a visit from my father soon followed. When he came to visit, we would go to a museum. It was something touristy for us to do, a way to formally introduce him to the unfamiliar place where I had chosen to plant roots. It also quietly assured him that the home I had chosen away from his own—the home he’d built as a former refugee chasing the American Dream, and the home where I was raised—was safe, even beautiful, and had the capacity for beautiful things: paintings from Renaissance masters, Egyptian sarcophagi, Attic pottery, and Chinese jade. These, at least, were things that I loved, and it comforted us both to have me near them.

Success, at least, meant safety, and there was no more obvious a marker of success than the frivolity of fine art.

I chose to study ancestries that were deemed important—heritages that were treasured—because I didn’t know the history of Vietnam, my ancestral homeland, before French colonization and the war that brought us to the US. As far as I knew, Vietnam’s pre-colonial history was hardly worthy of a footnote in the volumes dedicated to the human past and its many glorious civilizations. The country’s history is entirely subsumed under “Southeast Asia,” which, apart from Angkor Wat and the Khmer civilization, is in turn engulfed by the shade of the much larger, more revered East Asian civilizations of China, Korea, and Japan.

And it wasn’t only the Western gaze that made my fatherland appear so small and unmemorable: I never heard stories about Vietnam’s past from my parents either. Growing up, I always assumed that it was just another thing from our shared past that was blighted by the war and the nothingness it left behind—at least, for those of us who escaped. To ruminate on the past is to count the losses that survival required that we forget. And because I never had to bear that burden, I knew there were limits to what I could ask of them.

Finding a home in the history of another part of the world eased so much of my wanting. There was no dearth of stories in the cradle of civilization; everything I could ever want to learn, I learned, and that luxury was insatiable. It felt comforting to be among ruins, artifacts proving the existence of a story, even if it wasn’t mine.

In the museum, I showed my father my favorite objects from the places my education said created the most ingenious art: the Assyrian lion hunt reliefs and the 15-ton guardian lions of the Temple of Ishtar at Nimrud in Ancient Mesopotamia; the Nereid Monument from Ancient Lycia in modern-day southwestern Turkey; the chariot horse at the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos; and the lion statues of Amenhotep III from Egypt’s 18th Dynasty.

My father quietly marveled at them and took his pictures.

•

We made our way upstairs to a sprawling gallery floor, and at the very center—in the middle of the gallery—we found a small, standalone vit- rine with three shelves holding about five objects inside: a vase, an incense burner, and a few earthenware bowls. “Vietnam,” read the case label.

We flanked either side of the case, staring in. It was the first time I was introduced to our people in art.

The object descriptions were sparse; none of them had any stories behind them other than the vague, undecided aesthetic attribution, “Chinese influence?”

“What, is our stuff not good enough to steal?” I joked.

We laughed and moved on, turning our attention to the more impressive South Asian and Chinese collections that dominated the floor. There were other things to admire, even if they weren’t our own.

Our tradition made a little game out of our longing: count how many artifacts were ours, even when we already knew there was none. I wondered if my father could have been the only person in the building who was haunted by this absence.

“An art museum is a great place to be a refugee,” Lev Golinkin wrote in the opening of his essay “Guests of the Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa” in The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives. “In a museum, everyone’s a ghost.”

Some more than others.

•

My parents knew Vietnam only in wartime. My mother was born in the dying years of French empire and came of age with the nascent Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam—the country born after the 1954 Geneva Conference along with North Vietnam and the kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia. Our history, my mother told me, was not taught because it was still being written.

When the Republic surrendered to the North in 1975, the only country my parents knew was dismantled to build a new one. A new flag was raised, streets were renamed, and scores of the dead Republic’s citizens either fled, were “re-educated”—like my father—or were executed.

Many in my parents’ generation are committed to forgetting because grief is an intolerable animal. In their silence, a new nation rewrote the record.

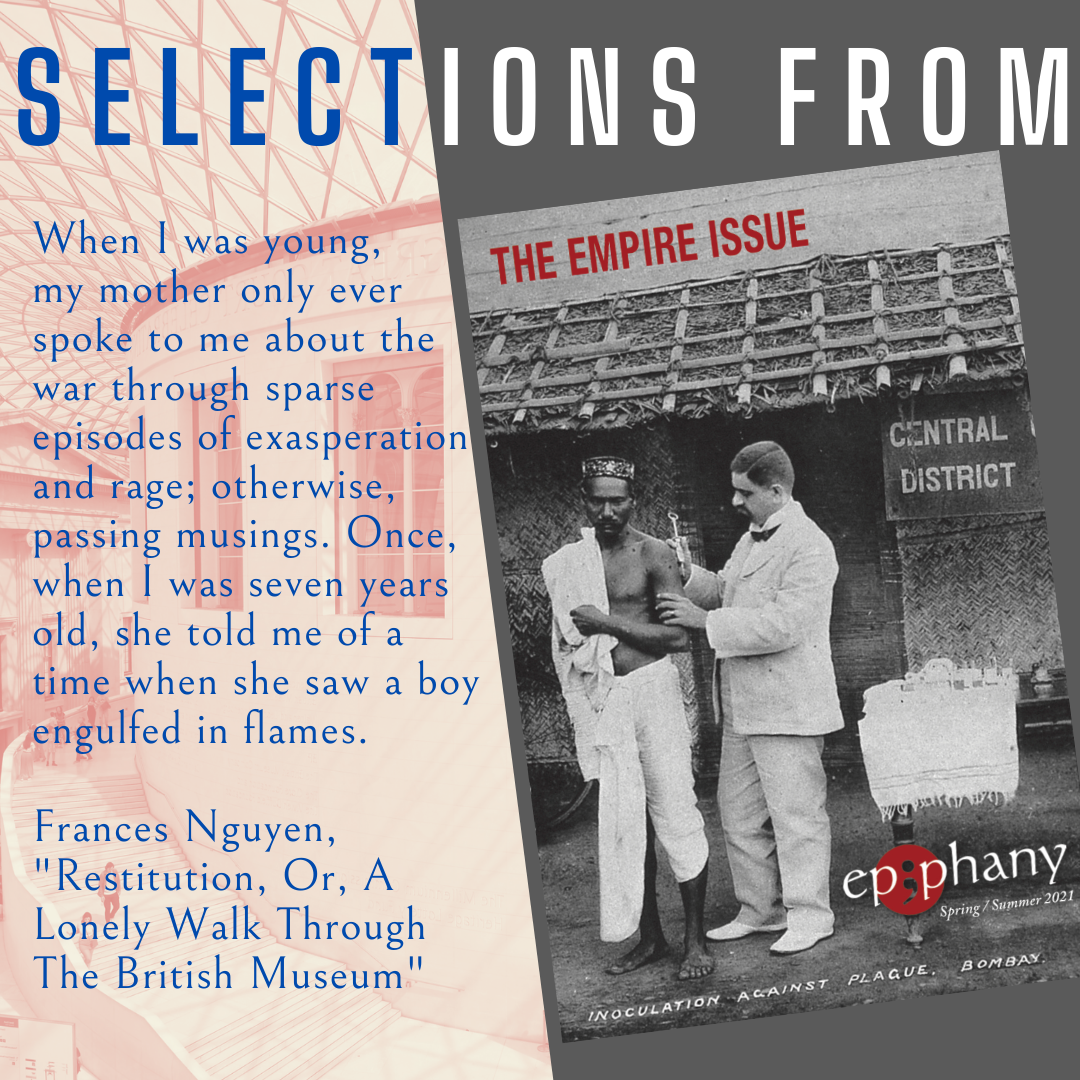

But it is ultimately time that changes the story. When I was young, my mother only ever spoke to me about the war through sparse episodes of exasperation and rage; otherwise, passing musings. Once, when I was seven years old, she told me of a time when she saw a boy engulfed in flames running through the street. I would later draw the scene in one of my free-write stories in the second grade, which prompted a parent-teacher conference.

Decades later, I would ask her about him again.

“Do you remember that boy, Mom, or did I just make him up?”

“It wasn’t a boy,” she replied. “It was a grown man. It was a soldier who killed himself in front of everyone, and no one reacted; no one could. And then there was a disabled veteran who killed himself with a grenade.”

Several hours later, she texted me, “Actually, there was a boy. He died of burns because a rocket hit our neighborhood.”

When I moved back from London, I told my mother about the museum visit with my father and that paltry display of our heritage.

“We used to have big bronze drums,” she said sitting up on her bed, arms outstretched reaching for the corners of the room. “They were priceless.”

But she couldn’t recall more about the drums, and I didn’t ask. She didn’t know where they were now. Eventually, she would need to be reminded of their existence at all.

•

Eight years later, I returned alone to the British Museum, on a swelter- ing summer day when the museum could only offer some air-conditioned galleries; the other rooms instead had floor fans whirring like bayou airboat propellers, kneading the hot, humid air around the rooms.

After visiting my beloved objects, I went back to the upstairs gallery to admire the little vitrine where our patrimony lived conspicuously as literal window dressing for patrons moving between the China and South Asia wings. But when I got there, not a single object attributed to Vietnam was on display anywhere in the museum.

Two docents, a security officer, and two staff manning the informa- tion desk assured me that there was “something, somewhere mixed in” the South Asia side of the gallery. I went through the gallery three times, slowly, meticulously, perspiring as I combed through every object one by one. But there was nothing. It was almost as if I had imagined them being there to begin with.

I pulled out my laptop at a table at The Old Crown, a pub off Museum Street—a ritual stop after a day spent haunting the museum’s halls—and went on the museum’s website. Thirty pages of search results for “Vietnam” yielded hundreds of samples of coins, banknotes, and little else. Did I really imagine them? Memory can be an unreliable witness.

But you rarely forget the things that scar you, even the smallest tears.

Eventually, I found them: the blue and white fish ewer, the emerald green-glazed phoenix, the mottled glazed stoneware—all were accounted for in the museum’s inventory, but none of them were displayed on the floor.

They existed, at least. Not that any visitor that day would’ve known but me.

Room 33 of the British Museum was reopened in 2017 by Her Majesty The Queen as the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery of China and South Asia. The gallery had gone through a major refurbishment to “present a new narrative for China and South Asia.” Everything else was written out.

It felt like an embarrassment of loss, a scorned inheritance. The refu- gee generation to which my parents belonged shed everything when they escaped — who they were, what they believed in, what they dreamt for their futures. I had hoped that a beautiful image of the country they left behind might’ve managed to escape with them. There were shards here and there, but not enough to satisfy a collector in the West. Not beautiful enough to join the plundered collections of a world-renowned, encyclopedic museum like this one.

As Golinkin wrote, “You’re better off staying invisible.”

•

My father wasn’t wrong about the souvenirs.

Upon the museum’s post-lockdown reopening on August 27, 2020—after its longest closure in peacetime—two of my chosen stops on our tour that day became featured objects along the museum’s new guided route “Collecting and Empire,” which explores “the complex, varied—and sometimes controversial—ways in which objects have become part of the collection.” The route was created as one of two major gestures from museum director Hartwig Fischer in response to the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations around the world that followed.

“You just have to do the right thing,” Fischer told The New York Times.

The route offers no mention of the Parthenon Marbles (also known as the Elgin Marbles after Lord Elgin, London’s ambassador to the Sublime Porte who ordered the removal of the carvings from the Parthenon in 1802) or Hoa Hakananai’a, the massive stone monolith carved by indigenous Rapa Nui (Easter Island) islanders said to carry the spirit of a prominent tribal leader or deified ancestor—otherwise, the spirit of their people.

Fischer may have acknowledged some looted items in the collection, like the Benin Bronzes: a collection of thousands of plaques, masks, and figures wrought from largely metal, ivory, and wood, seized when British colonial soldiers invaded the West African kingdom of Benin in 1897.

But he wouldn’t be pressed about them.

“This collection is not based on looted objects,” he contested. Most of the eight million objects in the museum’s possession were, allegedly, acquired by scientists and “collectors with genuine passion and interest in world culture.”

“I think that’s what’s really at the heart of this institution,” he said.

Never look for worthiness in a museum of stolen souvenirs.

•

When Enotie Ogbebor, a visiting artist in residence at the British Museum, saw the Benin Bronzes on display there, he said that they carried the aura of war trophies. “To see them in isolation, far away from home, kept for onlookers to gawk at without any real understanding of what happened— it’s like being a witness to your family story told wrongly,” he told The Washington Post.

David Adjaye, the architect behind the National Museum of Afri- can-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., felt much the same way as Ogbebor when he first saw them. “It burst immediately the image of these cultures that I had, that somehow it was kind of underde- veloped,” he told The New York Times. “It smashed through that and showed me here is the artistry, and the mastery of culture.”

He is the architect of the planned Edo Museum of West African Art, the new museum in Benin City, in what is now Nigeria. It will house the 300-some items on loan from European museums, including the British Museum, which is participating in a $4 million archaeology project to exca- vate the planned museum’s site. In 2025, the Bronzes could be returning home—if funding holds.

As Adjaye envisioned it, the new museum would not be “a container of curiosities” but a true institution of the 21st century, intended to place the Bronzes within their original cultural context and reconnect Nigerians with their past. “It has to be for the community first and an international site second.”

I can’t conceive of such an idea: having your culture reflected lovingly back to you. What home could a stateless people give their patrimony, anyway? In Vietnam today, the only history Vietnam’s Communist government cares to preserve is the country’s victory in “the war of US aggression.” Without land, artifacts are just as displaced as their people.

•

Years after I left London, I found one of the drums at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Tucked away behind glass, in a mixed display of artifacts from across Southeast Asia, I discovered a moss-colored drum, a sprawling bronze disk that looked like a warrior’s shield, adorned with four small frogs symmetrically positioned along its border, and a star at its center.

The Bronze Age Đông So’n drums, which have been found widely dispersed across Southeast Asia—displaced, even—are typically adorned with geometric patterns, scenes of daily life and war, animals and birds, just like my beloved Assyrian reliefs. Whenever I visit the museum today, I pay this one a visit, in tribute to my ancestors.

There’s a project in Australia by two diasporic Vietnamese artists to revive their sound. RE:SOUNDING, by James Nguyen and Victoria Pham, is described as an “attempt to metaphorically raid colonial collections of museum artifacts, and to breathe a multidimensional and complex life back into objects that are stuck in clinical, Eurocentric collection rooms.” It’s a collaborative effort to create an open-access library of sounds with artists and performers around the world, reviving an ancient instrument and allowing it “to exist in another narrative than just being an artifact of an exotic culture.”

So far, Nguyen and Pham have only worked with a drum that was bought at private auction. They’ve been speaking with museums for years, but the administrative process to have an object in their collections loaned or used by outsiders is tedious and time consuming.

“There’s these institutional structures around care for a collection in museums,” said Nguyen. “But these structures of care don’t necessarily prioritize letting objects have a spiritual existence within the cultural communities they belong to, of having a resonance and connection to contemporary life.”

The project isn’t giving up hope, though. The plan, ultimately, is to record using drums currently held in museums.

Before I discovered this project, I never imagined the drum as anything more than an inert object behind glass, one that I knew belonged to my people but was so far from home that it didn’t have meaning anymore. It didn’t have resonance beyond what my exhausted mother once conjured from her heartbreak.

I wonder now what it sounds like. When I hear it for the first time, will I recognize it against my ear? As I imagine the music, I feel my mind drifting, dreaming of what story it will sing of my people, who and how they were long before anyone in faraway lands cared to know about them. I wonder how I will change after I hear it, how, at long last, I might come home.

—

Frances Nguyen