"Memorial Pool" by Parker Menzimer

Laura Riding’s poem “Prisms” begins: “What is beheld through glass seems glass.”

&

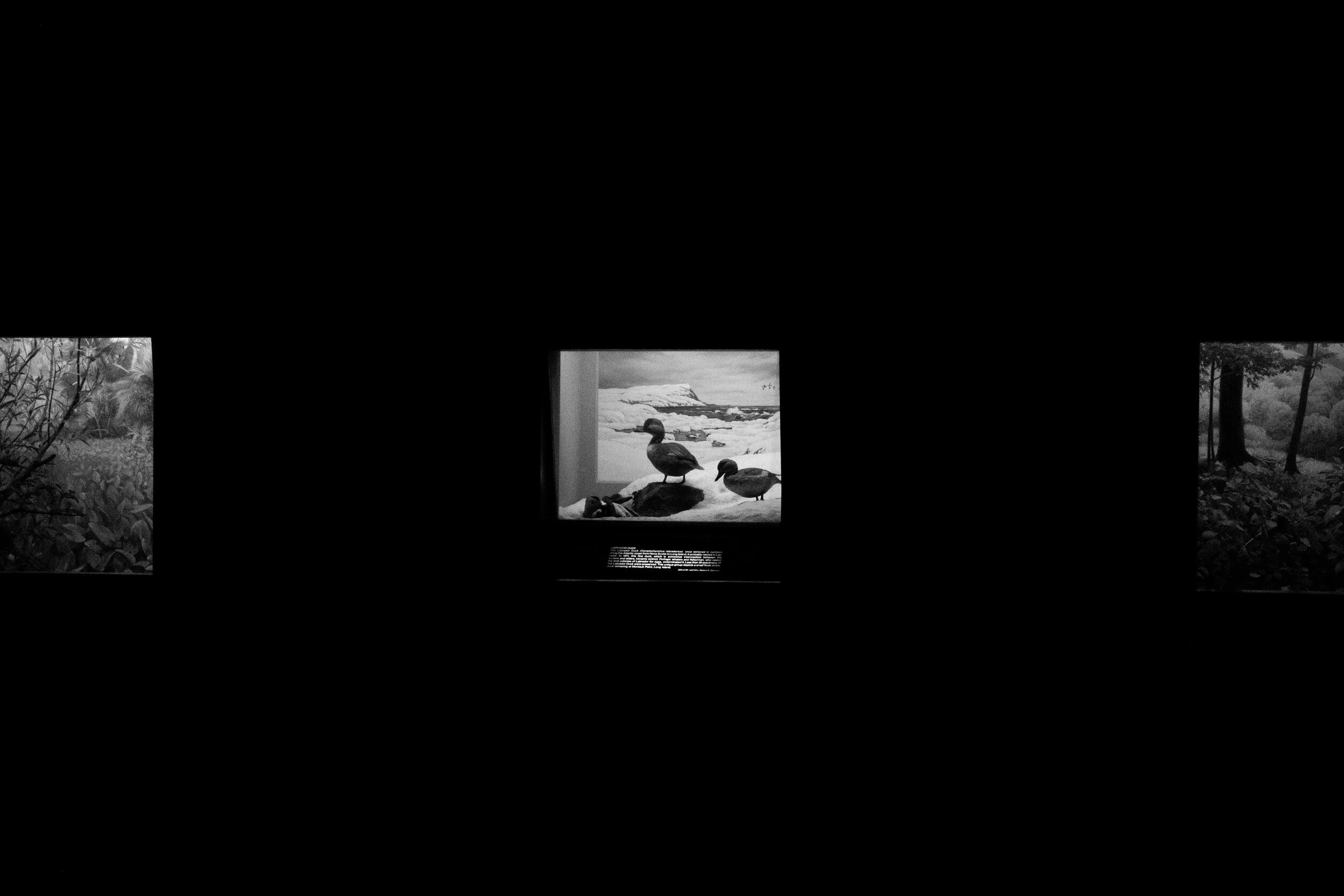

On a crisp afternoon mid-autumn I sat on a remote outcrop over the Hudson River, watching a pair of sturdy ducks bob and dive in a reflecting muck. I gazed across the water toward a wide estate smoldering in brilliant foliage, before turning my attention to a tugboat pushing an unloaded barge downriver. The birds continued to dive. This place is perfect, I thought, for a pit stop on a long migration. More than anything else in that picturesque landscape the ducks lodged in my memory.

&

Plate 332 of John James Audubon’s famous double-elephant folio, The Birds of America, describes Fuligula labradora, the Pied duck. For this account of this rare northeastern fowl, Audubon had to rely on descriptions from other ornithologists; he notes with apparent disappointment, “No birds of this species occurred to me when I was in Labrador.” His son, on a separate expedition, discovered “several deserted nests” that belonged to a raft of Pied ducks. A group of empty nests recovered by his son; this is as close as the elder Audubon would come to encountering Fuligula labradora in the wild. His folio text is mediated by absence and motivated by an impulse toward recoverability. The Pied duck emerges from the author's writings as a print emerges from photo-sensitive paper; what is shown seems to be a duck, but it is only a provisional mediation of light by a fixed negative.

Elmira Star-Gazette. Unadilla, New York.

&

The section of river I gazed across feeds the Tivoli Bays. I had driven to the Hudson Valley to visit my alma mater, Bard College, and to catch an exhibition at its Stevenson Library: Fruiting Bodies: The Mycological Passions of John Cage (1912–1992) and Violetta White Delafield (1875–1949). On my way out of the exhibit I stopped to examine a wall near the library’s first-floor restrooms, where artifacts of the college’s history, dating to 1860, were mounted. I browsed the prints, texts, and photographs, settling on a faded image of thirteen men standing and sitting in formal dress, with surnames inked nearby. Among them, at the group’s upper left, stood a stiff man of medium build. Next to his head, in an uneven script, was scrawled the name Griffith. Years before, my aunt had suggested that our relative, a certain John Hall Griffith, had attended Bard when it was an Episcopal seminary called Saint Stephen’s. But my mother, a stalwart Californian, willfully removed from her East Coast girlhood—its climate, its circumstances, and its characters—never wholly committed to the premise. The shock of discovery, as I gazed at the diminutive Griffith, whose gray-white face had partly dispersed in the photograph’s ambiance, cured me of doubt. This was my great-great grandfather.

Mounted archival images of St. Stephen’s College. Stevenson Library, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

&

A camera constructs history

by way of imagination

&

In 1860, at six months of age, John Hall Griffith left Lanneli, Wales, with his parents, David and Elizabeth Griffith. The family landed at 810 Walnut Street in Elmira, New York. Upon arrival they likely spoke some or little English (even today, Lanneli is Wales’s largest Welsh-speaking enclave). John Hall attended the Elmira Free Academy, now called the Ernie Davis Academy after the alumnus who made sports history as the first Black footballer to win the NCAA’s Heisman Trophy, in 1961.

John Hall went on to become an ordained minister. He studied at Saint Stephen’s, in “Annandale on the Hudson,” and later at the Seabury Divinity School in Faribault, Minnesota, established in 1858 as a mission to indoctrinate American Indians in the Episcopal tradition. In 1864, several decades before John Hall’s arrival, the school dropped its missionary objective and moved within the borders of Faribault to the site of the present-day Shattuck-St. Mary’s School, “on the bluffs above the Straight River.” At Seabury, John Hall met the woman who would become his wife, Eleanor Lovisa. Following his studies he returned briefly to New York, taking a position as a pastor in Albany, before settling in Pennsylvania’s Northern Tier, first in Sayre, and later in Plymouth, where he served as the Vicar of Saint Peter’s Episcopal Church for thirty-eight years. A newspaper clipping from the Wilkes-Barre Record, printed in John Hall’s lifetime to celebrate his tenure at Saint Peter’s, states that he was “held in high esteem by his congregation and the townspeople,” having been “active in community and county benefit drives.” He was “well known as a fisherman,” a passion he pursued in the various small cities where he lived, always near a major river.

&

Later, my friend Garrett and I were just returning from a walk along the train tracks near Elmira's eponymous college. I had collected a battered railroad spike that Garrett spotted while I fiddled with my camera. (Orange rust had bloomed in the spike's every crook and bend.) Garrett told me that while traveling in Poland he had visited several Jewish cemeteries near an ancestral site outside of Białystok. During the Holocaust, he said, the graveyards were razed by officers, the markers decimated and remade by imprisoned Jews into cobblestones for the roads of the death camps. Some fragments still bore traces of Hebrew engraving. Garrett had pocketed one such stone. Back on the sidewalk, we passed a disheveled and abashed college student, whose inquisitive pit bull smelled Garrett’s hand, learning something of his history.

&

Pied duck was one of several early common names for what is now called the Labrador duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius). Most existing specimens were collected in the early 1800s. The century wore on, and the bird was sighted with increasing infrequency by hunters and birders along North America’s Atlantic coast, from the Delaware Peninsula to Newfoundland.

Signage (“twintiersstrong”). Pietro & Son Restaurant, Elmira, New York.

&

In “The Monuments of Passaic” (Artforum, 1967), Robert Smithson describes a construction site along the Passaic River on a Saturday: “That zero panorama seemed to contain ruins in reverse, that is—all the new construction that would eventually be built. This is the opposite of the ‘romantic ruin,’ because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built. This anti-romantic mise-en-scene suggests the discredited idea of time and many other ‘out of date’ things.” Those “out of date” things might include the romantic ruin’s surest ally: poetry. Much has been said of the landscape that might have preceded the landscape that rose into ruin. Centuries of English-language poets have tried to address that place.

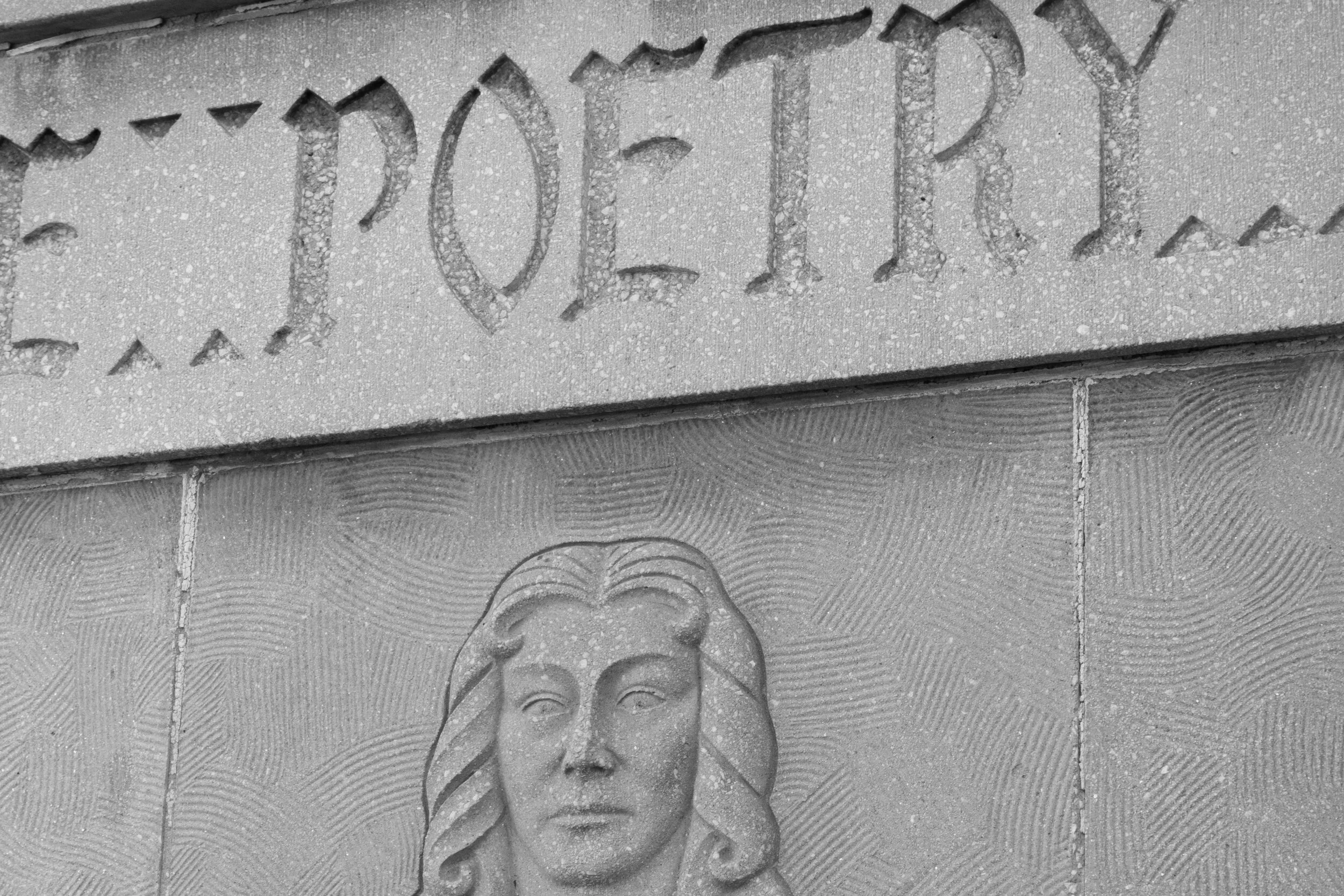

“The Seven Fine Arts” (detail). Elmira Collage, Elmira, New York.

&

The problem with cameras

is that the light is already working—

so why are we?

&

In 1980 Burning Deck Press published My Life, Lyn Hejinian’s seminal Language poem. In its eighteenth section the poet writes: “Memory is the / money of my class.” Of all the puzzling ideas among the poem’s 1,444 lines, I’ve puzzled over that one the longest. How to read the word class in a poem seems to account for an unremarkably white, middle-class California girlhood. I have wondered if Hejinian really meant something more like milieu, to invoke the trope-y poet who lives in a “genteel poverty” endemic to her trade. This reading implies something I have otherwise thought: that a poet's memory is her greatest asset, so much so that, if prudent, she will come to guard it jealously, and mete out its fruits judiciously. It is in the snare of that jealous relation, a binding to circumstances that are increasingly irrecoverable, and irreconcilable to language, that a poet begins to recognize her status.

&

In 1891, insurance agent and amateur ornithologist William Dutcher (1846–1920), of Brooklyn, made a substantial scholarly contribution with his “The Labrador Duck: A Revised List of the Extant Specimens in North America with Historical Notes.” Of the duck’s apparent scarcity, he writes, “There are but few naturalists or sportsmen now living who have had any experience with the Labrador Duck in life, and these are one by one passing away.” He continues: “During the period from 1860 to 1870, when an active lookout was kept for them, none could be obtained.” At the time of his writing, although he was not certain of it, the Labrador Duck had been extinct for at least thirteen years.

&

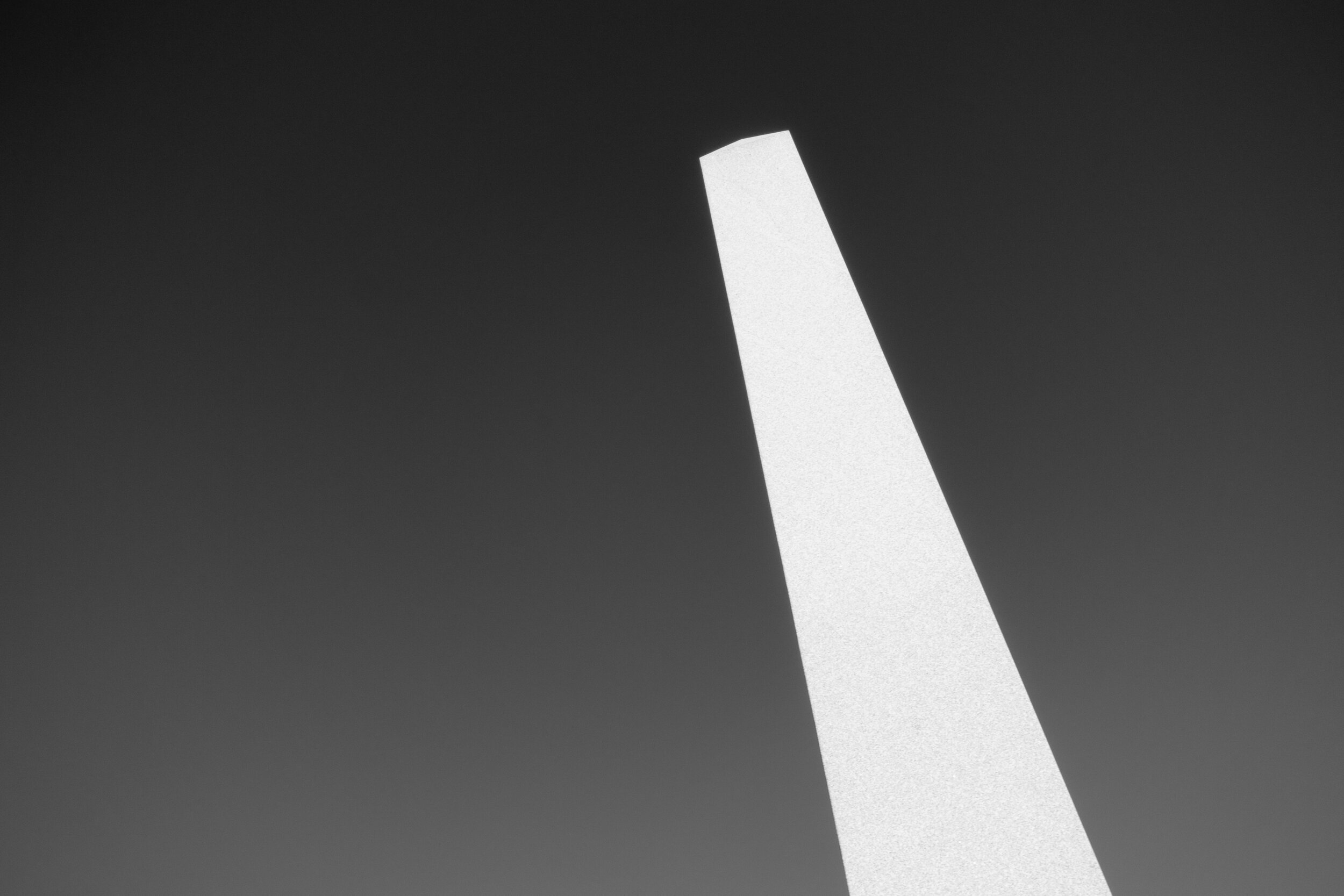

Garrett and I drove through the orderly suburbs on Elmira’s west side, passing brightly painted Victorian homes, sitting pert on generous lots. Lawn signs signaled support for local political candidates whose allegiances were suggested by the presence or absence of certain typographic flourishes. One sign read #twintiersstrong, a reference to the shared economy of Central New York’s bottom-most and Pennsylvania's topmost regions; business in Elmira had flagged under the weight COVID-19—the city’s downtown, like many across the United States, was effectively closed. The hashtag marked a site where materials, ideas, and sentiments had densely accrued. This was language strangely denatured: a word or short phrase made into plastic material. Like all plastic material, it would eventually be legible only as irreducible waste. In my mind’s eye I flipped #twintiersstrong on its end, making it an obelisk. A hashtag is like a tombstone, around which related markers are gathered. It can become a site of elegiac activity, and it can also be desecrated.

Obelisk. Elmira College, Elmira, New York.

&

In Dutcher’s “Historical Notes,” a series of interviewees express surprise at the Pied Duck’s apparent disappearance.

“The Labrador Duck I procured without much trouble," remembers George A. Boardman of Calais, Maine. "I had shooters all about the coast of Grand Manan and Bay of Fundy. . . . It seems very strange that such a bird should become extinct, as it was a good flier."

He regrets having kept no more than two specimens, acknowledging that his later attempts to procure additional examples were unsuccessful: “I wrote to all my collectors, but the ducks had all gone.”

Stuffed Labrador ducks “formed into a group with characteristic surroundings” (Dutcher). American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York.

&

Woodlawn Cemetery, a pastoral graveyard built in 1864, is Elmira’s “Top Attraction,” per Trip Advisor. Its primary draw for many will be the plot where Samuel Longhorn Clemens is interred. He lies beside his wife, Olivia Langdon, to whom he was introduced in the mid-1860s, around the time he first used the pen name Mark Twain.

Clemens claimed to have taken his nom de plume from a contributor to the New Orleans Picayune who, as Clemens liked to tell it, died in 1863: "As he could no longer need that signature, I laid violent hands upon it.” The American historian Ernest E. Leisy notes, “I have examined the files of the New Orleans papers during the period when Clemens was a pilot on the Mississippi, but I find no evidence of anyone’s using the sobriquet ‘Mark Twain.’” The German academic Horst Kruse calls the ranging debate around the origins of Clemens’s pen name “an ideal situation for mythmakers, amateur psychologists and storytellers,” noting that even its most prominent theories “can hardly satisfy the scholar.”

Olivia Langdon was the daughter of a prominent businessman who made a small fortune in coal. She was an abolitionist from an early age and was something of a socialite in the Twin Tiers; she introduced Clemens to the circle of liberal reformers among whom they moved for the rest of their lives. Upon their marriage, the couple moved to Buffalo, living off the Langdon family fortune, which afforded Clemens the chance to pursue a middling career as a newspaperman and stakeholder of the Buffalo Courier-Express.

Clemens and Langdon summered in Elmira, and a curious octagonal writing studio, built for Clemens on a Langdon farm property, now sits on the campus of Elmira College, which was a college for women when Olivia was a student there. One hundred–odd years after Clemens and Langdon met, my aunt, whose mother’s family name was, coincidentally, Langdon, enrolled at Elmira College. It became coeducational in 1969, the year she dropped out to live as a hippie in Colorado.

Signage (“MARK TWAIN NEXT RIGHT”). Woodlawn Cemetery, Elmira, New York.

Civil War buffs might be more interested in the National Cemetery, an addition to Woodlawn located at its northern end, where the remains of Confederate prisoners of war are interred. The associated prison camp was a deadly complex dubbed “Hellmira” by its inmates. Thousands perished there, mostly of malnutrition or infectious disease; those who survived were given a one-way ticket to the South in 1865. A fundraising organization, Friends of the Elmira Prison Camp, is now at work on “the reconstruction of an original camp building.” Organization literature indicates that the building’s original purpose remains “unknown at this time,” implying that its purpose might become clear when the reconstruction is complete.

Signage (“Welcome to Elmira: Honoring the Past and Building the Future”). Elmira, New York.

&

John Hall, the Saint Stephen’s graduate, my great-great-grandfather, was buried in West Nanticoke, near Plymouth, Pennsylvania, ninety miles south of his childhood home of Elmira. An entry on Find a Grave states that some of his major accomplishments in the Twin Tiers included participating in “the committee for the Soldiers and Sailors Monument” and “the acquisition of Huber Field from the Glen Alden Coal Co.” This entry and two photographic portraits were supplied by Find a Grave user “Bob,” whose avatar is a photograph of a Weimaraner (caption: “Buddy”). As of late 2020, Bob had added 1,703 memorials to Find a Grave, averaging three per week since creating his account.

&

Nicholas Pike of Brooklyn, New York, notes his last encounter with the Labrador Duck: "In 1858, one solitary male came to my battery in Great South Bay, Long Island, near Quogue, and settled among my stools. I had a fair chance to hit him, but in my excitement to procure it, I missed it."

George N. Lawrence of New York City reminisces: “At one time I remember seeing six fine males, which hung in the market until spoiled for the want of a purchaser; they were not considered desirable for the table, and collectors had a sufficient number." He muses: “No one anticipated that they might become extinct, and if they have, the cause thereof . . . was surely not through man's agency."

&

En route to Clemens’s Woodlawn plot, I spotted an obelisk near the path: “Griffith.” I took a picture of the marker’s base and made a rubbing in my notebook of a large, ornate G near its peak. As an offering I left the railroad spike and a bit of blue chalcedony, a gift from my sister that supposedly activates the throat chakra. I urged the Welsh immigrant David Griffith, John Hall’s father, to get in touch.

Headstone (“Griffith”). Woodlawn Cemetery, Elmira, New York.

&

The reasons for the Labrador duck’s extinction are a matter of debate, though it is likely that the explosion of human activity on the Atlantic coast in the nineteenth century exerted sufficient pressure to extinguish the population. Like other “minor” “New World” extinctions, the disappearance of the Labrador duck will present mainly as a decorative prop or standee on the dynamic stage of settler-colonial history—it is certainly no more than a brushstroke on the painted curtain that hangs behind the more dramatic incidences of the Columbian Exchange. A duck’s disappearance figures in history’s rising action only obliquely. A mass death that only enlivens a larger dramatic structure. It is setting; it is not scene. What pressure does its absence exert on the landscape?

&

Later I learned from my great uncle that the Griffith at Woodlawn is not a relative. David Griffith was buried fifteen miles away, in Corning.

&

The problem with cameras

is that they’re trash eventually

&

Today, a deadly prison is situated just across the street from Woodlawn Cemetery. The Elmira Correctional Facility, a New York State maximum-security penitentiary, occupies an imposing brick complex perched atop a hill, set back about five hundred feet from a barbed wire fence. In the weeks before my visit, according to several news clips, the Elmira Correctional Facility had the highest incidence of COVID-19 of any prison in New York.

&

According to Dutcher, the last known Labrador Duck was shot by “a lad” in Elmira on December 12, 1878. Dutcher claims that Dr. W. H. Gregg, who heard of the shooting, identified the bird using only “the head and a portion of the neck.” Gregg allegedly preserved the remains but lost them in a subsequent move to New York City. His claim is subject to debate. In an email, Chemung Valley historian Kelli Huggins told me that Gregg “had an eyebrow-raising backstory. Between snake oil sales, bank fraud, [and] other bird misidentifications, he turns out to not be the most credible source.” Elmira’s location, almost three hundred miles from the Atlantic coast, makes it unlikely that the last Labrador Duck was spotted there. But a monument to its purported existence, by artist Todd McGrain, has been installed near the site of Brand Park Memorial Pool, by the marshy banks of the Chemung River.

Labrador Duck monument (detail). Elmira, New York.

Parker Menzimer is a poet and editor. He is editorial director of Topos Press and an MFA candidate at Brooklyn College, where he is a Truman Capote Literary Trust Fellow. His words have recently appeared in BOMB, Tiding House, Second Factory, and elsewhere.