"Graduate School Meditations" by Michael Barron

Kimball is a small corner building with a glass façade and aluminum siding. It is steps from Washington Square Park, the heart of the New York University campus. On a recent balmy Monday morning, I came here by bike to pick up an ID keycard that I had applied for online. I was sweating beads and grateful that I had already submitted a photo. All I had to do was pick it up.

It wasn’t that easy. At the entrance was a line and a small crowd. The latter fed the former, but gatekeeping the two was campus security. When I tried to get in line, one of them asked for my screener.

I assumed they meant the mandatory COVID test that I had taken the previous week. I pulled up the results.

“This isn’t the screener,” she said. “I need to see the screener.”

I shook my head. I shrugged. She instructed me to download the NYU Mobile App, then had me click on an icon of a smartphone with a medical cross in the middle. “That’s the daily screener test. A green color means you pass. If you get that, come back to me and I’ll let you in.”

“And if I don’t pass?”

“Go down the street and get tested,” she said, “immediately.”

The questionnaire was a familiar y/n, much like the one used to fill out a weekly unemployment insurance form. I was experiencing no fever and had not left the city in two weeks. Green. Back in line, I waited to receive my card, which was handed to me in a hard acrylic case. Practically bullet-proof.

*

The university was committed to a COVID-safe campus. A few weeks prior, it had issued a mandatory schoolwide COVID-test. I had been selected to go on the first open day. While I stood in a line to get my upper nasal cavity swabbed by an elongated Q-tip, I read from Index Cards, a collection of essays by the writer and photographer Moyra Davey. Of watching people’s behavior she writes:

On the subway downtown to the New York Public Library in search of Mary Shelley’s diaries, I begin to notice subway riders absorbed in writing of their own: a woman paying her bills, another marking pages on which the word draft is stamped in large letters…There is a man folded over his crossword… and children doing their homework. A woman wearing orange velvet gloves clutches a small yellow pencil.

Standing in line for both the COVID-test and for the ID, I see people hunched over phones, with their ears to phones, with their hands gripping phones, gesticulating like mimes. Only in the COVID-test line do I see two other readers, one with a book, the other flipping through a stapled print-out. I thought of the subway, which I hadn’t ridden in months.

*

I submitted my application to NYU’s Fiction MFA program this past December when the Coronavirus, by then already spreading from its origin in Wuhan, China, still had yet to be identified or significantly reported. It wasn’t until after the New Year did it start receiving international attention. By the time I received word of my acceptance, in the last week of February, the Coronavirus had already reached New York.

A week later, I attended a meet and greet between faculty and prospective students at NYU’s Lillian Vernon Creative Writers House. By then, on everyone’s minds was the growing prospect of a quarantine, but it wasn’t yet enough to stop people from congregating at the punch bowl and food platter; no one then wore masks as they munched and drank in one-foot conversational proximity.

What was being discouraged was contact, the practice of which clashed with habit. I was introduced to Zadie Smith who offered her hand for a shake, only to hesitate once I grasped it. “Whoops,” she said, softly pulling away, “we aren’t supposed to do that anymore, are we?”

*

The event was the last time I had eaten from a communal snack bowl or attended an indoor mingle. It was the last time for many things normal. The idea of a future, like attending graduate school in the fall, seemed incomprehensible during a widespread pandemic, as well as the social upheavals and political tensions that followed.

It had been my plan to continue developing the fiction sample I had submitted as part of my application, but I struggled to continue with a story set in a world made impossible by our newfound realities. There will always be political and social unrest, but a pandemic filters everything—we are all characters in its story.

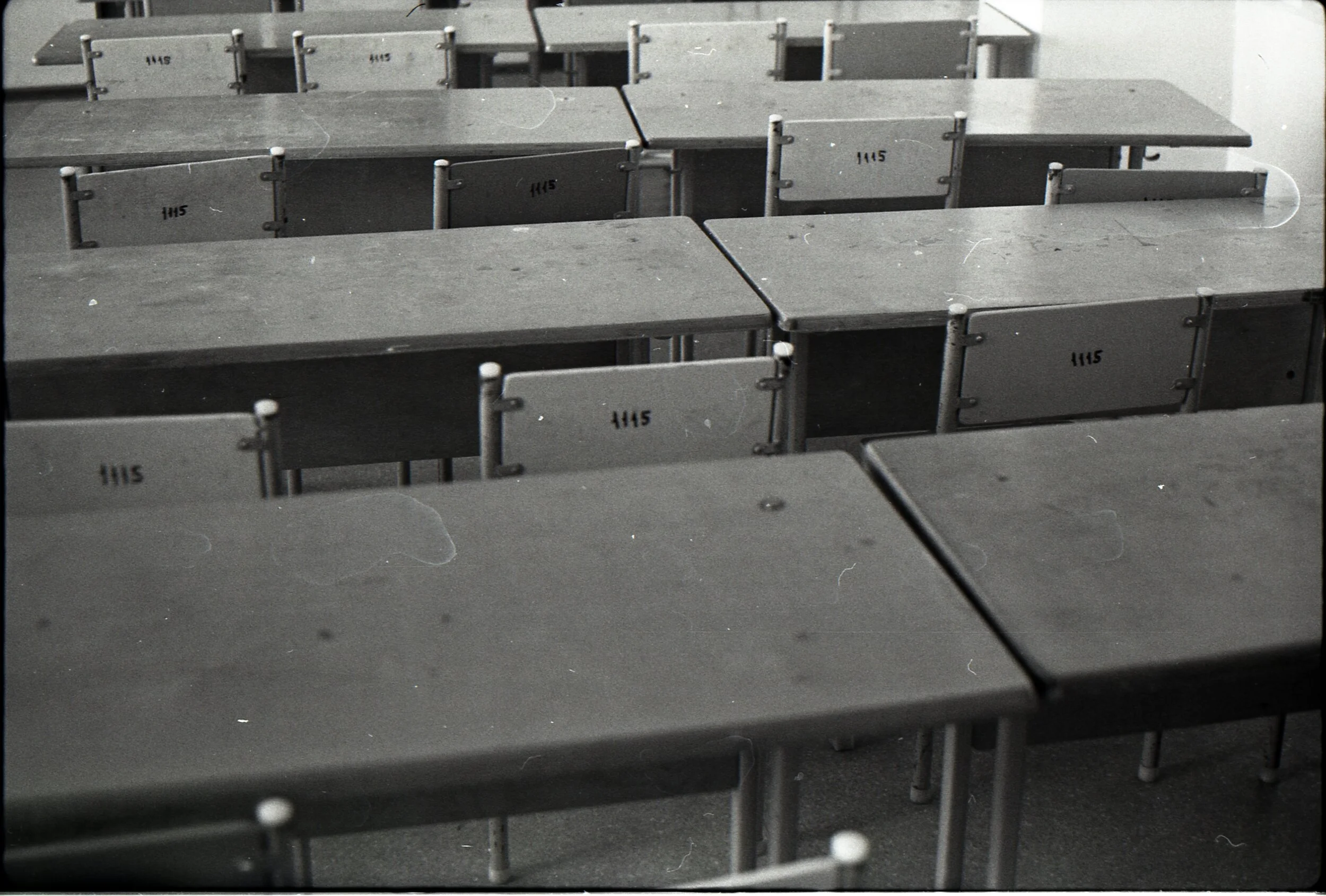

To break out of my writer’s block, I started keeping a daily journal. The purpose was less to document, than to write as if I were dribbling a ball or treading water. I found periods distracting and wrote long single sentences detailing my previous day. Other times I would caption photos I had taken, a sort of ekphrastic exercise. In both, I avoided bringing in anything topical. I was fighting to restore autonomy to my writing that had been invaded by reality. I felt as though my prospects of being a student of fiction depended on it.

*

The day after I received my ID, I logged in to the virtual student orientation hosted by the staff of the creative writing program. This time there was no punch bowl, no famous writer’s hand to shake. The director, Deborah Landau, began with an apology that nodded to these circumstances: “this is usually a celebratory event,” she said, “with a big party and everything. But we’re still here, and that’s what’s important.”

It wasn’t entirely a sober gathering. Though this was going to be anything but a normal semester, the staff ensured that things would continue as optimally possible, including virtual and arranged office hours. To encourage and broker introductions between students, meet-and-greet sessions followed the orientation, with some even joining from far-flung locations. One student from Tel Aviv noted “class for me starts at 11 pm, but what am I going to do?”

In another group, a woman asked if anyone had gotten any writing done since the pandemic. A couple people replied that they had worked on stories and poems; others had been less productive. I told of my dilemma and how, in the absence of working on the novel, I had taken up daily journaling, calling it the most and least amount of writing I have ever done. The woman spoke back up: “Honestly,” she said, “I’m grateful to be in school right now. I could use the distraction.”

*

I finish Davey’s book and summer ends too. The temperature drops. In my first class in fifteen years, I make a clumsy and apologetic greeting. I say “this is my first class in fifteen years.” I learn quickly how personal a Zoom can be. Your face fills everyone else’s screen. You cannot hide. Two people who had volunteered to submit their work for the first workshop were met with overly eager critiques. You could see the humility rise on the writers’ faces. I thought they were brave, I felt for them. I would be in their position soon enough.

Michael Barron is a writer and editor who lives in New York.