"Fight or Flight: On Adrian Piper and the Escape to Freedom" by Hawa Allan

“Would you like to know why I left the U.S. and refuse to return?

This is why.”

—Adrian Piper, Escape to Berlin

In November 2006, the conceptual artist and analytical philosopher Adrian Piper discovered that she was on a watch list of suspicious travelers maintained by the United States Transportation Security Administration. She was on a brief trip back to the States from Berlin—where she’d fled the year before—when she found out she was on a list of “selectees” (as the T.S.A. calls it) whom airport staff are authorized to pull aside at security checkpoints and subject to further screening. This enhanced screening process could include anything from thorough pat-downs to hand-inspecting luggage to testing one’s items for explosives. After making this discovery, Piper left the United States and—until her name is removed from this list—has vowed never to return.

Piper makes only brief mention of this incident in her 2018 autobiography, Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir. While her formal classification by the U.S. government as a “suspicious person” is the reason Piper will not return to the country of her birth, it isn’t why she left in the first place. For Piper, being a “suspicious person” was nothing new. As an African-American woman who “looks white,” Piper was not only accustomed to being eyed with suspicion and enhanced scrutiny, but had also regularly plied such racial ambiguity for her internationally-acclaimed art. Instead, it was her academic colleagues who effectively drove her out of the country. Piper describes a toxic combination of whisper campaigns, ostracism, and administrative harassment that made her term as a tenured professor of philosophy so intolerable as to give rise to an illness that brought her to the verge of death.

This is Piper’s story. Think Get Out, but set in a university.

In that light, it makes sense to read Escape to Berlin as part of the canon of slave narratives—that is, insofar as slavery in the United States has been formerly abolished but continues to have ongoing deleterious effects on the lives of Black Americans. A slave narrative is not just a memoir written by a slave, it’s a literary genre, and every genre has its tropes. With the slave narrative, the reader can expect to find horrific details of the writer’s captivity—gruesome both in fact and in the context of the seeming mundanity with which humiliation and cruelty are doled out and are supposed to be submissively suffered. The reader then rides the writer’s narrative arc into escape and fugitivity toward “freedom.” The slave narrative also doubles as a work of literature and historical document, rewriting history through the lyric voice of a formerly muted slave, who is recast as an active protagonist in a story where they were meant to remain a silent, background object.

Piper’s Escape to Berlin deviates from the slave narrative genre in some key ways, however. For one, while subverting official versions of history, the slave narrative is often also a political statement, published to aid abolitionist aims by soliciting the reader’s empathy and, ideally, political solidarity. Escape to Berlin, though, does not seem to have any agenda other than its mere existence. “You can choose to close this book right now,” writes Piper, “and lose nothing.” Throughout the memoir, Piper repeats what she thinks about the reader’s reaction to her plight: “I don’t care.”

*

Another twist in Escape to Berlin’s otherwise typical slave-narrative plot is that the memoir does not start with captivity, but freedom. Unlike the denouement of Piper’s story, her initial freedom was not at all hard won. In fact, she was oblivious to it. Piper doesn’t recall any conscious sense of having felt “free”—referring, in this case, to the lack of any perceivable limitation on her internal sense of self, worthiness, or possibility. Growing up an only child of two doting parents, she was raised to believe she was important. “There were no siblings to envy me, or compete with me, or bully me, or ridicule me,” Piper writes. “So I did not experience those things, and I also did not learn how to inflict them on my peers.”

Piper proclaims she was a real child. She was carefully cultivated and deeply loved. And she had never witnessed or been subject to physical abuse. (She did once talk back to her uncle, prompting him to raise his forearm into what “would have issued in a backhanded slap in the face if he had completed it,” but she had no idea what he was doing and “just looked up at him, uncomprehending.”) Her parents also never commented on her physical appearance and instructed relatives to refrain from doing so as well—a silence that resulted in Piper not realizing she even had a perceived appearance until her adolescence. “Up to that point,” she writes, “I had felt invisible to the naked eye. Not absent, not ignored; quite the contrary. It was just that what I received attention for had nothing to do with the way I looked.”

How Piper looked, however, was the subject of unending interest to those outside her family’s protective shelter. In fact, a concerned grade school teacher once asked Piper’s parents if Piper knew she was Black. She was the daughter of a light-skinned African-American couple, with her father’s branch of the family having broken off from estranged relatives who decided to pass as white; her father was so adamant about affirming his status as an African American that he refused the wealthy inheritance offered to him by his relatives. So, for Piper, race was always a conscious affiliation, not an essentialist identity. Race was apparent in the words of other Black kids who taunted her, wondering what she was doing on “their” New York City block as she walked to school, or among her white friends who asked their white peers to guess her racial identity as a kind of parlor trick. Throughout all of this, Piper seems to have organically arrived at an understanding of race that aligns with its actual definition—a social construct rather than a biological fact.

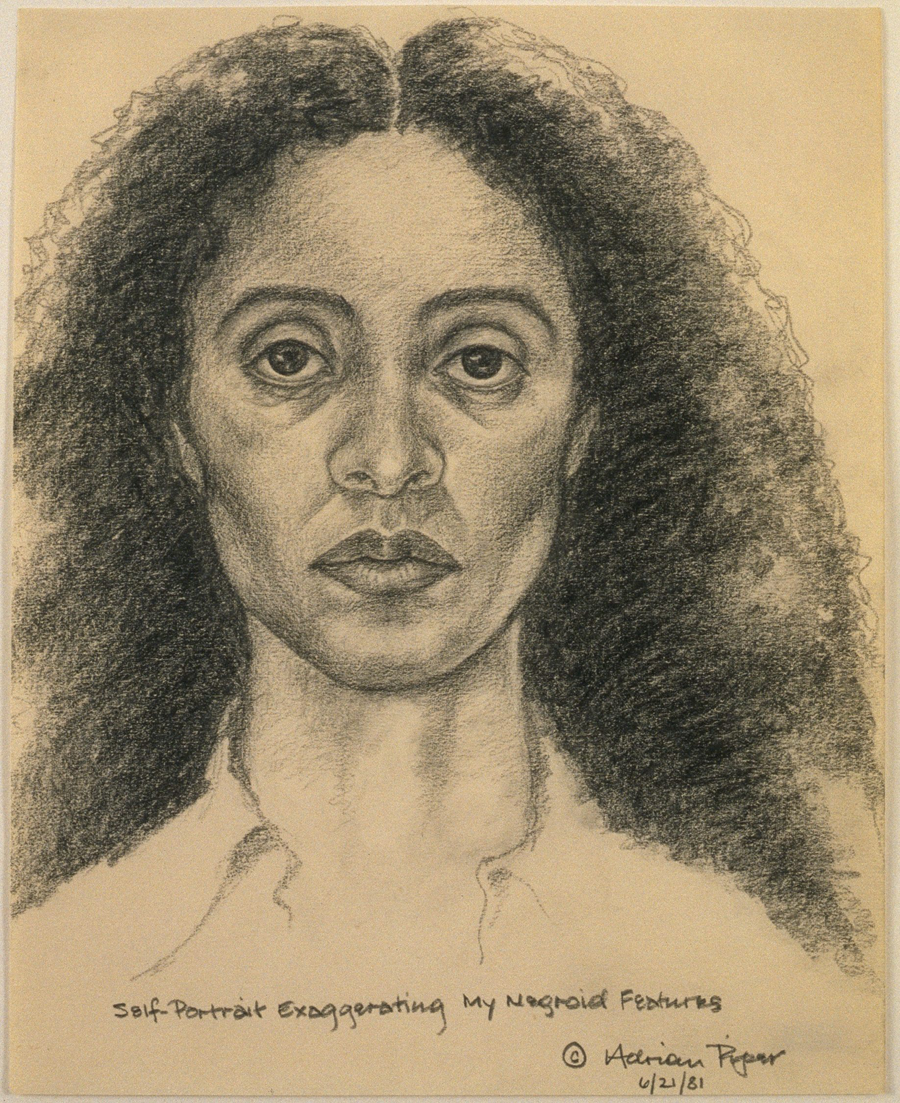

Given this background, it makes sense that Piper gravitated toward conceptual art, which emphasizes the ideas generated by art over its aesthetic value. Her most noteworthy works are confrontational, immersing viewers in the experience of her artwork by prompting them to question their own racial filters and other biases. Among her early works of the 1970s is a series called Catalysis, in which Piper bewildered unwitting members of the public with guerrilla performances. In Catalysis III, she went shopping at Macy’s with a placard hung across her body that read “wet paint,” referring to her own clothing which was coated with sticky white paint. For Catalysis IV, Piper walked the streets of New York with a white rag stuffed into her mouth, her cheeks distended as the rest of the cloth spilled down past her chin. Both performance pieces have been interpreted to address whiteness, the first as an artifice and the second in terms of its silencing effect.

Adrian Piper, Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features, 1981. Pencil on paper. 10" x 8" (25,4 cm × 20,3 cm). The Eileen Harris Norton Collection. © Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin.

Piper’s later works explore similar themes, if more explicitly. Piper’s My Calling (Card) #1, is an actual card she would carry around and hand out to unsuspecting bystanders—unsuspecting, that is, of her status as a Black woman. It read:

Dear Friend,

I am black.

I am sure you did not realize this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark. In the past, I have attempted to alert white people to my racial identity in advance.

Unfortunately, this invariably causes them to react to me as pushy, manipulative, or socially inappropriate. Therefore, my policy is to assume that white people do not make these remarks, even when they believe there are no black people present, and to distribute this card when they do.

I regret any discomfort my presence is causing you, just as I am sure you regret the discomfort your racism is causing me.

Sincerely yours,

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper

Though much is made of Piper’s later announcement that she had “retired” from being Black, it’s clear from her artwork—as well as her memoir—that this was not a delusional bid to occupy a post-racial fantasyland, but a tongue-in-cheek provocation that acknowledges the man-made nature of “race.” She was always clear-eyed about the historical and contemporary burdens that this concept has placed on African Americans.

*

“One wakeful night,” Walter Bradford Cannon wrote in his scientific diary of the physiological effects of adrenaline evoked by stress, “the idea flashed through my mind that [such effects] could be nicely integrated if conceived as bodily preparations for supreme effort in flight or in fighting.” The Harvard physiologist wrote this entry in his diary in 1911, and is known to be the first scientist to describe the body’s fight-or-flight response: a manifestation of the sympathetic nervous system’s reaction to a perceived threat to one’s survival.

Cannon initially observed such physiological responses in cats, whose digestive functions would cease when they were subjected to stress, and later observed similar responses in football players, in whose urine he detected high levels of blood sugar following a high-stakes game. Cannon also wrote: “These changes—the more rapid pulse, the deeper breathing, the increase of sugar in the blood, the secretion from the adrenal glands—were very diverse and seemed unrelated.” He surmised, however, that they could be derived from a common combination of stimuli—fear and rage.

The physiological responses Cannon first catalogued flush the body with enough stamina to either fight off the source of the perceived threat or to flee from it. It’s a biological survival mechanism that apparently derives from an ancestral contention with the much bandied about saber-toothed tiger, and now lingers as an instinctual response to anything from driving at a crawl-pace through rubberneck traffic to workday encounters with a nasty, brutish boss. What in fabled antiquity might have shored the body with sufficient energy to avoid being mauled has evolved in modern times to steel humans against the perceived threats of frustrated advancement and financial ruin—two chronic societal fears that perpetuate the very physiological responses which, when continually triggered, will not save you from immediate harm but instead end up killing you slowly. From the inside.

*

Piper’s gateway into the world of philosophy was Immanuel Kant, in whose Critique of Pure Reason she found herself so immersed in the summer of 1971 that she periodically put down her reading to look at herself in the mirror, touch her face, and check to see if she was still there. Surely, she was already aware of the illusionary world of appearances, of how one’s perception or immovable spectacles obscure one’s knowledge of the “thing-in-itself”—the true yet ultimately unknowable reality that gives rise to the phenomena we observe. She documented her summer of Kant in a piece titled Food for Spirit, where she recorded herself reading passages of the text and snapped her reflection in a full-length mirror for a series of prints in which her image gradually disappears.

Already steeped in her vocation as an artist, Piper soon started taking her philosophical studies more seriously, eventually obtaining a PhD from Harvard and teaching in the field. It’s this period, and her experiences in academia thereafter, on which Escape from Berlin dwells. Piper’s narrative animates the disassociation between theory and practice that she kept stumbling upon within her many teaching departments, including her time occupying a sixth and final post at The College—the label she applies to Wellesley, deigning to refer to it by name. During her sojourn in academia, Kant recedes as a philosophical forebear and Socrates emerges as a luminous, albeit distant, beacon. This is not because Piper’s colleagues would engage in critical dialogue by earnestly asking questions intended to clarify the arguments of their peers. Rather, she found they aligned themselves with the gormless mass of Athenians, who bristled at any challenge to their utterances—challenges they made sure to silence with punishment.

Her advisor in graduate school didn’t appreciate how Piper took it upon herself to question and refine the presuppositions underlying his own work in her dissertation, and retaliated by, among other things, damning her with “faint praise” in letters supposedly supporting her teaching applications. Attempting to make sense of that particular scenario, Piper decided to be optimistic, to chalk up that incident to one exception among what would surely be a general experience of collegiality and camaraderie among her fellow philosophers.

So, she moved forward. At her next post, she started a women’s group for graduate students and staff to ensure gender inclusion and she provided detailed comments and critiques of her senior colleagues papers. “I had intended my criticisms […] to contribute to the production of first-rate work that could withstand those criticisms.” She was denied tenure.

As she moved on once more, and then again and again, Piper still tried to maintain that these particular encounters were with people who deviated from the Socratic norm of rational and civilized dialogue. “At that time, it never would have occurred to me that the entire field of academic philosophy itself could be a deviation from that norm,” Piper writes. “After teaching in six departments, I am now much more receptive to this hypothesis.”

In short, Piper continued to come across a series of “string-pulling authoritarian bullies.” She was much more of a pessimist by the time she had become the first African-American woman to be tenured at The College. But this shift in perception alone would not spare her. At The College, they called her campus-wide anti-racism work “self-serving”; they spread rumors that she didn’t like the chair of her department; they excluded her from departmental meetings and disparaged her to the dean; they reneged on their purported commitment to support her research and practice in the fields of philosophy and art; they denied her applications for sabbatical and administrative support for her work. And after two failed lawsuits Piper had filed for discrimination, harassment, and retaliation, they finally terminated her tenured faculty position.

Throughout this ordeal, she suffered a drastic blow to her health and was diagnosed with a liver disease her doctor labeled “progressive, irreversible, and fatal.” The College, Piper recounts, accused her of feigning her illness, and, before they fired her, overrode doctor’s orders to adjust her teaching schedule to avoid exacerbating her symptoms. Due to these actions—in addition to overcharging her for health insurance premiums, falsifying long-term disability application documents, and withdrawing health benefits—Piper concluded that The College wanted her dead. This was why, gradually and secretly, without any warning, much less formal goodbyes, Piper had her belongings packed up and shipped to Berlin, where she soon followed. She was already settling there when The College gave notice of her termination.

*

In traditional Chinese medicine, every organ of the body is associated with an emotion. The liver, in this lineage, is linked with anger, which if repressed is said to build up in the organ and foment disease. Piper doesn’t discuss this in her memoir, but does note that her “progressive, irreversible, and fatal” liver disorder miraculously cleared up following her flight from The College to Berlin.

Perhaps her experience is related to the relatively less discussed and third automatic bodily reaction to stressful stimuli—freezing. Like the proverbial deer in headlights, one might feel their heart race, ears prick, and pupils dilate only to find themselves frozen in place, rather than reflexively fighting back or running towards safety. To freeze, experts on psychosomatic medicine advise, is to pause in preparation for the next move. But when the adversary is not an oncoming car or, say, a saber-toothed tiger, but an onslaught of seemingly organized, administrative harassment, the time between the initial instinct to freeze and the ultimate move to fight or flee—and, thereafter, restore the body to equilibrium—could elapse, as in Piper’s case, for years.

The College never formally responded to Piper’s legal claims, which, in any event, were filed after the statute of limitations had passed. In fact, her will to communicate directly—whether by discussing philosophical precepts or alleging discrimination and harassment—were never answered with meaningful words, but more bureaucratic retribution. And the spoken words of her colleagues, Piper noted, were not intended to convey truth but to evade it. In addition to Piper’s pessimism, this was yet another reality that dawned on her slowly.

“[H]aving been raised in an environment in which people meant what they said,” Piper writes. “I lacked the ability to distinguish between sincere utterances and merely polite or politic ones.” She had adopted her parents’ selected mode of self-defense in a racist society, which was to “stand behind your word,” maintain your integrity, and “falsify the stereotype.” In her striving to actually mean and do what she said, to ensure her actions aligned with her speech, to, as Kant would have it, act in accordance with principles she would will to be universal law, Piper assumed that everyone else surely must be doing the same. This turned out to be a false presupposition.

Unlike herself, Piper writes, “most viewed philosophy as a way of achieving job security and professional status.” And, by contrast, “they did what they felt was necessary in order to attain those goods.” At every step, while those around her chose “financial security or gaining professional acceptance” over “the norms of Socratic dialogue,” Piper, instead, chose “trouble-making questions” and “the secure foundation of careful and thorough research.” And those who did not make a similar choice, which seems to have comprised most of her colleagues, succumbed to “the desperate, predatory climate in which string-pulling and authoritarian bullying flourish.”

So, armed only with high intelligence and shrouded in naiveté, Piper was completely unprepared for the quagmire of office politics and its particular brand of procedural violence. Like all violence, the office-politics version is abetted by silence and complicity, but it is exceptional for being inflicted through the medium of denial-stamped forms, “lost” invitations, and the arbitrary withholding of purported entitlements, among other paper-laced weaponry. For Piper, this is the crucial difference between concluding that The College wanted to kill her versus The College wanting her dead. Procedural violence gives plausible deniability to allegations of malicious intent and causation, two necessary elements for the case of murder.

*

I read Escape to Berlin both as a cautionary tale and as my own private vindication for all those roads not taken. Perhaps Piper was not simply refusing to refer to Wellesley by name, but by only referring to The College, was conceding to a pessimistic generalization of her negative experiences in the academy. However, I read her work to be not only an indictment of academia, but of all workplaces, which, in similar spirit, I will refer to as The Institution.

From PR firms to newsrooms to non-profits to law firms to courtrooms to classrooms, and even or especially in supermarkets and fast-food joints, The Institution in all its manifestations is a little fiefdom characterized by petty abuses of power where everyone is a wannabe overlord. The Institution always has a stated mission, which is proudly parroted in the words of those who labor on behalf of them, but The Institution is also always permeated and ultimately governed by an unstated mission, which everyone already seems to know but will never tell you. To be fair, I do remember soon after graduating from my own college, having been hired at one of The Institutions, finding myself on the receiving end of a number of conspiratorial winks from co-workers. I had no idea what they were trying to tell me only that they were hinting at something. Nonetheless, part of “playing the game” seems to entail never overtly admitting that you are, in fact, playing or that there is a game at all. As Piper writes:

“Only a gullible and self-indulgent windbag dissipates her strategic advantage by voicing her convictions, destroying her neutrality, and alienating her allies by implicitly challenging them to match her risky behavior by revealing themselves in turn.”

When you are admitted into the Institution, you are not just walking into a given building or a floor of a given building outfitted with offices and desks and chairs, you are entering into a construct—an otherworldly paradigm silently presided over by unwritten laws. These laws will not be found on The Institution’s website. Studying The Institution’s code of conduct will not help you. And high intelligence, passion, and curiosity—the very combination of factors that likely granted you admission into The Institution—may very well be your downfall. If you merely apply your high intelligence, passion, and curiosity to your written job description, the one The Institution said it was hiring you to fulfill, then you will, according to the unwritten laws, be under performing. You will have failed to comply with the unspoken rules to know your rank, stay in your place, and, effectively, seamlessly navigate The Institution’s entrenched minefield of egos.

Now, the “string-pulling authoritarian bullies” seem to know these unwritten rules, which they skillfully apply as they artfully dodge, sidestep, and lever themselves into positions from which they can then administratively intimidate those who would dare threaten their newfound status of relative overlordship. They seem to know that they have been hired for two jobs, not one, and will continue to maneuver up the ranks in order to secure as much compensation as possible for their stated role. When you are navigating The Institution as a woman or a non-white, especially Black, person, the unwritten rules of engagement to avoid appearing to overtly disrupt the preexisting hierarchy while diligently climbing over others to ascend it is further overlaid with the stigma of societal caste. One is to assume her rightful place at The Institution, not only in accordance with the job title, but also according to race and/or gender, which as a Black woman, is typically assigned to be somewhere towards the bottom.

Adrian Piper, Decide Who You Are #1: Skinned Alive, 1992. Three screen printed images and text on paper, mounted on foam core. 72" × 42" (182,8 cm × 106,7 cm); 72" × 63" (182,8 cm × 160 cm); 72" × 42" (182,8 cm × 106,7 cm). Photograph photo credit: Acey Harper/ People. Collection Margaret and Daniel S. Loeb © Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin.

This is not to say that it is impossible, as a Black woman, to claw up The Institution’s ranks, but given the enhanced scrutiny and surveillance your colleagues will instinctively subject you to on account of your race and gender, it will take a tremendous amount of energy; you will resort to perfectionism and over-performance, hardly leaving time for the maneuvering and machinations that string-pulling authoritarian bullies who are white and/or male would, due to the ample benefit of the doubt they are afforded, have much more time to attend to. “I learned from my parents my reflexive counter-reaction to being a constant object of suspicion and mistrust,” Piper writes of her striving to falsify the stereotype, “and having to pass the same test of trustworthiness with virtually every person I meet, in any capacity, every time I meet them.” So, even if you know about the “game,” not only would you not have much time or energy left to play it, but would anyone play the game with you—or, dare say, let you win? Or would they test you over and over and over again to re-confirm that you were an eligible contestant to begin with?

As a Black woman at The Institution, when it is all said and done, you must out-perform the written rules of your job, suss out and struggle to oblige by The Institution’s unwritten rules, and, if that weren’t enough, become a poster-child for The Institution’s nominal commitment to diversity and inclusion. So, not only are your opportunities for advancement continually questioned and even thwarted, but you are effectively getting one salary for at least three different jobs.

Alas, one more fine point: high intelligence, passion, and curiosity, especially as a Black woman within The Institution, may also become your downfall because this combination of factors poses a double affront. They threaten both The Institution’s entrenched hierarchy, which any highly intelligent, passionate, and curious person already has to contend with, and the overlay of societal caste. The dissonance is too great, and The Institution cannot hold. The epic battle has begun, and the question is begged: will you break through The Institution, or will The Institution break you?

*

Historical myth has it that a twelve-year-old Black boy named Jocko Graves who served under George Washington during the Revolutionary War was with the general on a cold night in December 1776 when he crossed the Delaware River to attack British redcoats in Trenton, New Jersey. The story is Graves had wanted to go along with Washington, who thought the boy was too small, and instead handed him the reigns to some horses and a lantern, instructing him to remain on that side of the river until Washington came back. Upon Washington’s return, the boy was still where he had left him, frozen to death with the reigns and lantern clenched in his fingers.

The myth of Jocko Graves is the origin story of the modern-day lawn jockey—a small statue of a Black man with cartoonish features and a horse-riding outfit—that became a popular, ornamental piece in many a suburban front yard. I call this factoid a myth because historians have deemed it apocryphal, as no evidence to its veracity, or even the existence of a Jocko Graves, has ever been uncovered. Despite the story’s dubious origins, the concrete endurance of the lawn jockey has given rise to debates over its larger meaning—whether as a notable effort to insert African Americans into a history they have been consistently written out of, or as an offensive caricature that further objectifies Black people by fashioning them into decorative showpieces.

If Graves ever existed, he surely would have been a slave. In his service to Washington, Graves would not have been fighting for his own freedom, but for that of the white settlers of the American colonies. Proponents of the important symbolism of the lawn jockey also point out that the statuettes may have been instrumental in the flight of fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad, with color-coded ribbons tied to their outstretched arms to guide fleeing slaves to “freedom.” Yet, it must be noted that the antithesis of slavery was, and perhaps continues to be, “free” labor. And suffice it to say that I have not found liberation within the confines of The Institution.

For me, the lawn jockey symbolizes the conundrum of being Black at The Institution. Do you soldier on, dutifully holding the reigns you have been given, a torchbearer shining light on your own endurance, standing still, stoic, and on display as The Institution’s evidence of its tolerance? And, if you continue to hold on, and do not drop the reigns, will you be rewarded for your patience, loyalty, and industriousness before you freeze to death?

*

Death is inevitable. Yet there is so much to distract us from this immutable fact. One diversion, it seems, is maintaining an affiliation with The Institution, which provides an ultimately false sense of safety and belonging. The Institution is part of what Piper calls “layers of wrapping,” around an internal revolving spool—one of her metaphors for the essential self. She writes:

“You are frozen in place by that unending length of woven fabric, wrapping itself ever more tightly and intimately around you: immobilizing you in a cocoon of commitments, expectations, demands, debts, obligations; dressing you in the need to fulfill them all successfully, and the desire for the rewards of doing so which they promise.”

And yet, as I found, the more you wrap yourself in The Institution’s cloak of safety, belonging, and prestige, the more you suppress that internal spool. “They devour your awareness,” Piper writes of successful social institutions, “filling it with their importance and the complexity of their functioning, and awakening your need to find your place within them.” So, you risk being suffocated by the very sanctuary from which you sought cover. That’s the thing about all those string-pulling authoritarian bullies: “They, too, are frozen in place and preoccupied by their revolving, rapidly ballooning outer surfaces, just as you were.”

However, unwinding myself from The Institution’s embrace has also felt like a kind of death, because “if you are really shedding all those layers forever, then you are on your own.” Just as the illusion of safety and belonging does not actually translate into security and acceptance, that feeling of death is not a physical death—it is actually a fear of freedom.

*

Though Piper chose to escape to Berlin, she didn’t necessarily find “freedom” there. Yes, she was free of the Athenians and their passive aggressive violence. Free, finally, to pursue her interdisciplinary pursuits in peace—which, not incidentally, resulted in her self-published opus Rationality and the Structure of the Self: A Two-Volume Study in Kantian Metaethics. In 2015 she was also the first African-American woman to be awarded the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for best artist in international exhibition. But Piper’s freedom is not a place. Her freedom, rather, is a sensibility that was carefully cultivated by her parents in early childhood, and I read Escape to Berlin, ultimately, as Piper’s love letter to them for loving her unconditionally. It is the freedom they instilled in her that she fled to Berlin to preserve.

“That The College went out of its way to break me and thwart my work itself engendered an enormous fund of material and inspiration for that work. […] It is almost as though an assault on my sense of self-worth automatically sprouts some regenerative creative output that heals it, much as new buds and shoots grow from the trunk of a tree whose branches have been clipped or broken.”

Escape to Berlin is a testament to this regenerative capacity, as it is a piece of art itself. The memoir, interspersed with family photos, poetry, and reproductions of artwork, is also bilingual, with the left-facing pages in German and the right-facing in English. The book does not so much narrate an escape to freedom, as it is a product of freedom. Piper is so free that she doesn’t care what I, you, or anyone else thinks. She didn’t even care to attend her 2018 show at the Museum of Modern Art—the largest show The Institution has ever put on for a living artist. And why didn’t she go? Because she vowed never to return to the United States until her name was removed from the government’s list of “suspicious persons.” In true form, keeping her word is more important than any kind of external validation. This is what her memoir relates about freedom and how to find it—from the inside.

Hawa Allan writes cultural criticism, fiction, and poetry. Her work has appeared, among other places, in The Baffler, the Chicago Tribune, Lapham's Quarterly, and Tricycle magazine, where she is a contributing editor. Insurrection, a weaving of personal narrative and legal history, is forthcoming from W.W. Norton.

Header Image Source: Adrian Piper, 2005 and Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir 2018 book cover © Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin.