"If I Had Your Face" by Yoojin Na

Whenever I ask my mother why we had to immigrate to America, she gives me the same answer: "It's because you and your sister are girls."

Growing up, I did not understand what she meant and wondered how my life would have been different, perhaps better, if I had been born a boy. Perhaps I would have been spared the difficulties and alienations of growing up undocumented. Perhaps if I had been a boy, I wouldn't have had to live with the curse of not belonging. Then, as I grew older, I began to glean into her insight through the details she shared with me about her early life.

As the eldest of eight, my mother did not dare dream of post-secondary education. What was a given for her younger brother was not an option for my mother. Instead of college, she took the civil servant exam and got an early start as a government contractor but she did not have a long career. At work, her male colleagues made open remarks about her body. The size of her bottom was a topic of frequent office discussion. Then, at the age of twenty-six, she met my father through a matchmaker, got married, and quit her job.

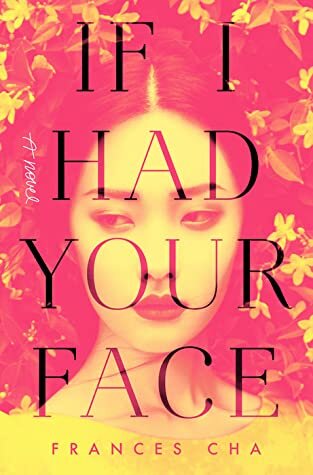

The story of my mother's life is not hers alone. Millions of women in Korea share the same fate. Despite all the emphasis Korean society puts on education and professional advancement, women are not expected to work past a certain age. To this day, the Korean word for "wife" is synonymous with "housekeeper." The travails of Korean women was made even clearer when I read Frances Cha's debut novel If I Had Your Face.

Though Korean by birth, Cha had a cosmopolitan upbringing spanning multiple continents. She has also served as a travel and culture editor for CNN in Seoul. With both a global perspective and a keen understanding of Korean culture, Cha scrutinizes the lives of four women—Kyuri, Ara, Miho, and Wonna—who live in the same low-cost apartment building in Seoul.

Miho and Wonna are both orphans. Kyuri is the daughter of a single mother. Ara still has both her parents, but they are unable to help with her mutism. With little money and no family ties to secure their footing in an ultra-competitive city like Seoul, these women have nothing but their own bodies to sacrifice. Ara works long hours on her feet at the beauty parlor. Wonna, too, works herself to such a state that she suffers multiple miscarriages due to stress. Kyuri subjects herself to painful plastic surgeries and entertains men at "room salons" to pay her bills.

#

Though I was born and raised in Korea, I only returned once as an adult. The summer after college, I landed a teaching gig in Gangnam, the posh part of Seoul, south of the river. Like Cha's heroines, I too lived in an officetel, a building full of small offices and efficiency studios. It stood on a wide and clean street lined with family-friendly convenience stores and cute sandwich shops. But this immaculate façade hid a certain seediness in plain sight. Right behind our officetel was the Jelly Hotel, which one foreigner described on Trip Advisor as a place for "discrete couples." Its neon pink sign shone bright above the roof of my building and caused me embarrassment every time I had to explain to a friend that I did not, in fact, live at a hotel that charged by the hour.

Later, I learned that the basement of my officetel housed a "room salon" like the ones that Cha's characters work in. After a few weeks, I became more apt at spotting them: They were uniformly underground and frequented only by men in suits.

Despite the insidiousness of these predatory practices, I never found myself a direct target. Perhaps my youth and status as an ex-pat shielded me from any personal mishaps. However, I was not spared from another kind of misogyny.

Each morning and evening on my commute, I'd pass by dozens of ads for plastic surgery clinics plastered all over the subway. Dramatic after-surgery photos revealed women's faces with exaggerated, Westernized features—ghost-white skin, double-lidded eyes, upturned noses, and narrowed jawlines. They were trying to achieve the kind of beauty standards that existed only in anime, an artform based on fantasies. In the subway car, I'd see real women who somehow held up to these impossible ideals. Even in a heatwave, their makeup and coiffed hairstyles would remained flawless. They’d spill out the train doors in short skirts, tights, and four-inch heels.

Those days, I wore little to no makeup and kept my hair in a messy bun. My go-to was a pair of ripped jeans and flip-flops. On more formal occasions, I'd sport my black ballet flats. Everywhere I went in Seoul, people asked me where I was from. The question confounded me since I had believed I was from Seoul.

One day, I asked the man I was dating what he liked about me and he replied, "You're so cute—chubby, and all." Given how kind he had been up to that point, I knew he wasn't trying to be cruel. He genuinely thought I was overweight and liked me in spite of it. Still, this came as a shock since I was still considered thin by American standards; even at my heaviest, I had not been larger than a size four.

I vowed never to step foot in Seoul again, and I've not gone back since.

#

A few years later, I had the opposite problem. Being too fat and homely by Korean standards did not prevent me from being "too young" and "too pretty" to be a doctor by American standards. The former I could understand but the latter always left me dumbfounded and hurt. Such innocent, backhanded compliments belied a dangerous assumption that beauty and intelligence in a woman were mutually exclusive. Why would a girl go to medical school and become a doctor when she could marry one? Why take on blood and guts when there are easier paths to security and comfort?

During my OBGYN rotation in medical school, I inadvertently caused a stir among the nurses by wearing the "wrong" scrubs. When I went to change for the OR, I noticed there were two separate piles. The blue scrubs were boxy and obviously too large for me. The green scrubs were smaller with a high, rounded neckline and a bit of a cinch at the waist. I chose the green ones since they fit me better. But as soon as I came out of the changing room, one nurse said to me, "Those scrubs are not for doctors. You shouldn't be wearing them." Another nurse disagreed. I should wear the green ones since I am a girl. I stood there awkwardly as they argued.

These days, when I step into the ER, I try to hide my femininity. I tie back my hair. I fill in my eyebrows so that they are thicker, more masculine. I wear sports bras to make me look flat-chested. I let whatever is left of my curves get swallowed under black, unisex scrubs. I hate myself for thinking this way because it negates all the good intentions of my parents. They took me out of Korea’s toxic culture, yet I could not stop seeing myself through its lens.

#

If I Had Your Face is not just the title of a book. It's a way of thinking for a whole nation of women.

In the book, Sujin, who works as a manicurist, wants to look like Kyuri so that she too can work in a room salon and make large sums of money. Kyuri is envious of Miho's natural beauty and talent. Miho is jealous of Ruby's everything—wealth, style, ease—all of which makes Ruby's beauty almost needless. Ruby, the only one who has everything, kills herself.

More disturbingly, If I Had Your Face does not offer up any tidy conclusions that I, as a reader, have come to expect. Does Kyuri overcome her alcoholism? Does Miho get revenge on her cheating boyfriend? Does Wonna deliver her baby safely? Does Ara ever get her voice back? Rather than answering these questions, the novel ends in media res with its four protagonists sitting together on the building's stoop and talking.

Initially, I felt annoyed and deprived by this denouement or lack thereof. Then, I realized my curiosities about their fates were irrelevant. The women have each other and—in their camaraderie—a safe microcosm where it matters not what they look like. Such communion of souls makes bodies, especially the shape of those bodies, irrelevant.

We could shave our heads, burn our bras, protest the patriarchy, and criticize the male gaze, but Cha suggests a simpler solution: true friendship among women.

#

After I finished If I Had Your Face, I called my sister Julie and lamented Korean beauty standards. Quickly, our conversation devolved into gossip and we talked about which of our friends had plastic surgery, and which ones had surgery but will never admit it.

“Remember when mom told us she’d pay for our plastic surgery?” I asked my sister. “What made us say ‘no thank you, we’re happy with what we’ve got’?”

“She might have called us fat or average,” recalled Julie, “but in the same breath, she would go on about how no man is ever good enough for her daughters.”

Images of Julie flashed through my head—the chubby toddler with sumo hair, the skinny school girl with a shy grin, the freshman dancer in her school uniform, the ultra-cool artist with a septum ring and purple hair, the bride beaming in a simple wedding dress, and the radiant new mom, holding her infant.

Julie has always been achingly beautiful, yet I had never told her.

Before we got off the phone, I finally did. She told me I was beautiful too, and for the remainder of the afternoon, I didn’t care what I looked like.

Yoojin Na is a writer and an ER doctor. Her work has appeared in Joyland, Quartz, The Rumpus, and others. She is working on a memoir that explores her identity as a 1.5-generation Korean American and a formerly undocumented immigrant. She currently lives in New York City.