"Family in the Foreign World" by Lana Spendl

by Lana Spendl

Suada stood in her curlers at the kitchen table and cut with scissors into a cardboard box. Her brother, who had remained with his family in Norway even after the war had ended, had sent her a package for her birthday. She ripped the last bit of the tape with her fingers and opened the flaps.

Inside, treasure awaited. Soaps, chocolates, two nightgowns. She pulled the gowns out quick—they were white and frilly, as she liked—and she held them up to her shoulders to determine their fit. They were perfect. And such a soft cotton, too. Aida, her sister-in-law, must have picked them out; her brother did not have an eye for these things. Suada almost turned her head to call out her husband’s name to show him. But her husband had passed a few years after the war. Alone, she focused again on the softness of her new garments.

A Kodak envelope was tucked in the box, between things, and she pulled it out and leafed through the images inside. The family around a table in Trondheim. Her brother over drinks with neighbors. He had gained weight. You could see it in the face, in the neck. Made him look older. Aida and the girls on the balcony. The girls were turning into women now: sixteen and eighteen. The oldest, Elisa, had even moved to Oslo for school. In the pictures the two wore black clothing. Black lipstick, black t-shirts, even their fair hair was dyed black. As if they were calling out to death. Elisa had a brow piercing. Suada paused and frowned.

When they were babies, she had carried their restless warmth in her arms and shown them to friends and neighbors. One night Aida had worried that swaddled Elisa had stopped breathing, and Suada had hurried over and unwrapped the child and moved her little limbs until the pink face burst into cries. Suada herself had never been able to conceive a child—this embarrassed her in her youth—and the two girls were the closest she had to offspring. Along with Aida and her brother, they were the only family she had left. She would talk to her brother about the girls’ clothing, she decided.

She unwrapped a bar of chocolate, broke off a row, and bit into it. She walked to the telephone, picked up the receiver, and returned to the table to dial their number. Maybe someone would be home. She sat heavily and popped another piece of chocolate into her mouth. The phone rang. She spread the pictures across the table, examining them as she chewed, leaning in to look. Then a girl’s voice, almost inaudible, answered in Norwegian. So quiet that for a second Suada thought she was overhearing someone’s distant conversation.

“Halo,” Suada enounced.

The girl switched to Bosnian. “Who is this?”

Suada’s shoulders relaxed. She filled her voice with cheerfulness. “This is Suada, calling from Sarajevo. To whom am I speaking?”

“Ah, Aunt Suada. It’s Elisa.”

“Elisa, dear! I was just looking at pictures of you. You have changed so much since I last saw you. Are you home from school this week?”

Elisa was silent.

Suada rubbed her tongue over her teeth to remove the chocolate. “Hello?”

“Aunt Suada, Dad left.”

Suada sat against the chair’s back, crossed one arm over her chest, and tucked her elbow into it for support. She smacked her lips. “When will he be back? I just got the lovely package with all the goodies. I’m already halfway through all the chocolate.” It wasn’t true, but it made for a good joke.

“Dad has left us.”

Suada’s lips stopped moving. An ill feeling filled her chest and rose up into her neck and cheeks. “He has left you?”

“He has met someone. She is four years older than me.”

Her lips opened to speak but no sound came. Her brother, with whom she had always been close, whose deep intonations she had expected to hear on the line, retreated from her like fog in the street.

“Aunt Suada?” the girl said.

“I cannot believe it. I just cannot.”

“He has been with her for some time. Some girl he met at work. Says he’s in love.” Then, more quietly, she said, “Mom’s in the bedroom. That’s why I’m whispering.”

“Goodness.” Suada imagined the spaces of that house now, the gloom, the obligation, the betrayal. And he was her brother. She felt complicit. She felt ashamed. Would they see her as being on his side? She felt the need to prove herself. But she did not even know the full circumstances. “Have you had any contact with him?”

“He left a note a couple of days ago, when he left. He disappeared in the middle of the night. Mom thinks he was planning it for a while. So many of his things around the house are missing. It’s like he hasn’t forgotten anything he would need.”

The girl was rattling the sentences off quick, as if she had said them again and again. Suada felt that she should ask to speak to Aida. But she did not want to. She could not imagine what Aida would unleash upon her. She could not defend her brother, but at the same time it would be painful to hear him attacked. Steeling herself, she evened her voice, filling it with an authority she did not feel. “Could I speak to your mom?” Then, quiet, she added, “Unless she wants some time alone, of course.”

“Yes, hold on,” Elisa said quickly.

Perhaps the girl was glad someone else, an adult, was going to speak to her mother. Suada, however, did not feel like an adult at the moment. She felt like a caught child. All eyes on her.

Movements and bumps sounded on the line. A door creaked. “Mama,” the girl said. “Suada je na telefonu.”

In the silence that followed, Suada imagined Aida pushing herself up from the bed with an arm, warm and wet with tears. She felt afraid to approach that body, even by phone.

“Halo, Suada,” Aida said. She sounded like someone waking up.

“Aida, draga, I’m so sorry to hear about what has happened.”

Aida said nothing.

“It breaks my heart to hear of the family being torn apart in this way. I had no idea, truly, that anything was wrong.”

“Suada, he has been absent for months now. Here, but not here. At the table in the mornings, not even hearing the questions I ask him.”

“I just cannot believe it. You seemed so happy when you visited last year.”

Aida sighed impatient. “Well, we weren’t so happy, Suada. He was happy to be back in Sarajevo with his boys from school. He was happy to see you. I was relieved that he was happy—I thought it might be a turning point—but it wasn’t. He was alive with you but he was not alive with us.”

“Mom, please,” Elisa said in the background.

“What?” Aida burst at the girl. “What? Just leave. Just leave me. You have no idea what I’ve been through.”

“But Mom—”

“Stop interrupting me. I’m tired of pretending everything’s pleasant. It’s not fucking pleasant.”

Suada winced. She had never heard Aida curse, especially not with the girls. Aida had always been proper, coiffed, perfumed. A perfect hostess. Making conversation over coffee and Turkish delights. Calming others.

“I’ve been cleaning his house, raising his children, washing his dirty underwear, and what do I have? Not so much as a goodbye. I don’t even know where the fuck he is.” Her pitch rose at the end of the sentence. “Said in the note he is taking this girl—this child—with him back to Bosnia. Do you understand we’ve been married twenty-three years? And suddenly everything is gone? I have no ground. I have no ground, Suada. I have no ground.”

Suada felt trapped between dark walls. She was not sure what to say. When her husband died everything had felt empty too, but this was different. This was intentional. “Do you know”—she began quietly—“do you know for sure that this is final?”

“What do you mean is it final? He left a letter saying he wasn’t coming back. I don’t know where he is. I don’t know anything. Do you understand? I don’t know anything. He did not respect me enough to tell me anything. Even if he were to contact me, I don’t know what I could bear.”

“Yes,” Suada affirmed. “Yes, of course.”

Suada was fifteen years older than her brother, and she had always welcomed him and his family with wide-open arms. She’d cooked for them, listened to them, invited friends over to see them and lingered in the corner of the living room delighting in their conversations. Her thick body stood rooted in their presence. Now she did not know who she herself was, nor what role to take. She wanted to offer a soothing hand, but their conflict felt like a river rushing forward without her. She could not reach out her hands to stop it.

She thought then that she could offer to call him, but an immediate resistance sprung up inside her. She could not offer hope, and she could not put herself in the middle. She would call him on her own, without announcing it.

“Are the girls okay?” she asked instead.

“How are they going to be okay?” Aida said. “Their father is fucking a girl their age.”

“Aida, please don’t say things you’ll regret.”

“Should I regret speaking the truth?”

“I only say this as someone who has regretted saying some things. Be kind to the girls. Be kind to them until the dust settles.” She was about to add, “Until you can see more clearly,” but she stopped herself.

“I’m not looking for advice, Suada. I’m not looking for opinions from others after what he has done.”

“Okay, Aida. I will not butt in. I’m very, very sorry. If you need anything, please call me.” A slight fear arose immediately—her own resources were so measly—and she hoped there would be no requests for money. Then she felt guilty at the thought, embarrassed.

“Very well, Suada.”

There was a strange finality to the sentence, as if it marked a break between the two of them. Disbelief arose in Suada at the thought that this one moment, this one day, could be the end of everything. Aida and her children had been Suada’s family. Suada always mentioned her to friends and neighbors—she talked about her and her brother and the girls at grocery stores and with people she ran into in the street—and everyone knew that this was her family, out there in the foreign world. Everyone always asked about them. Her only remaining relatives. Her only blood. Were they gone from her now? Loneliness spread through her like liquid through a napkin.

A click sounded on the line. Suada remained at the table, holding the receiver to her ear. The kitchen table sat oddly still. The whole world had settled into deep silence around it. The tone on the line started. She lowered the receiver. She eyed the pictures again—saw the girls in black—and their little black nails saddened rather than troubled her. So young and vulnerable before the world, they were putting on masks to find their way. She feared she could not help them, could not protect them from all that could fly up against a person in the space of a moment.

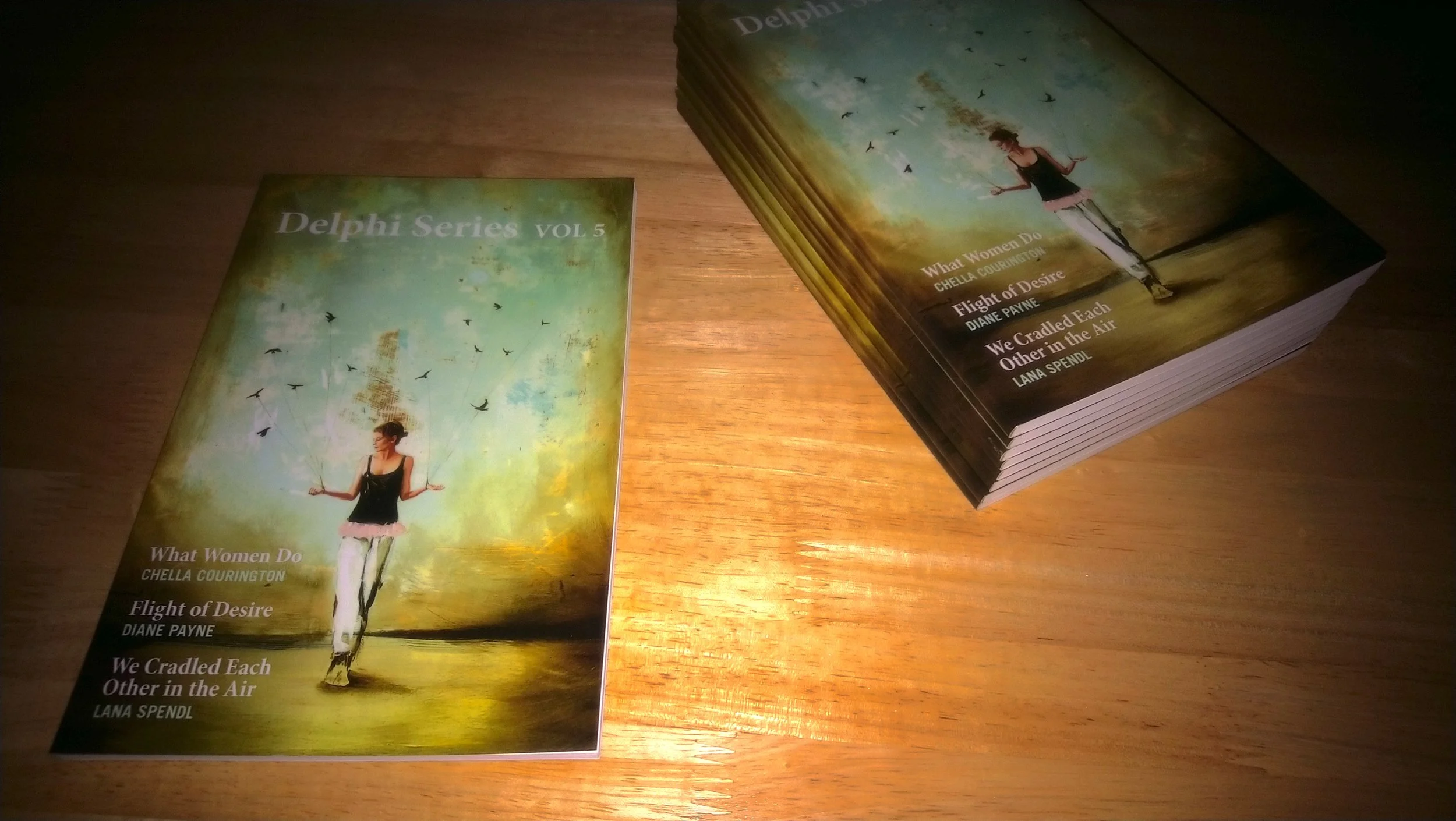

Lana Spendl’s chapbook of flash fiction, We Cradled Each Other in the Air, was published by Blue Lyra Press. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Rumpus, Hobart, The Greensboro Review, Notre Dame Review, Baltimore Review, New Ohio Review, Denver Quarterly, Zone 3, and other journals.