"Self-Discovery Through Honor Moore’s OUR REVOLUTION" by Brady Huggett

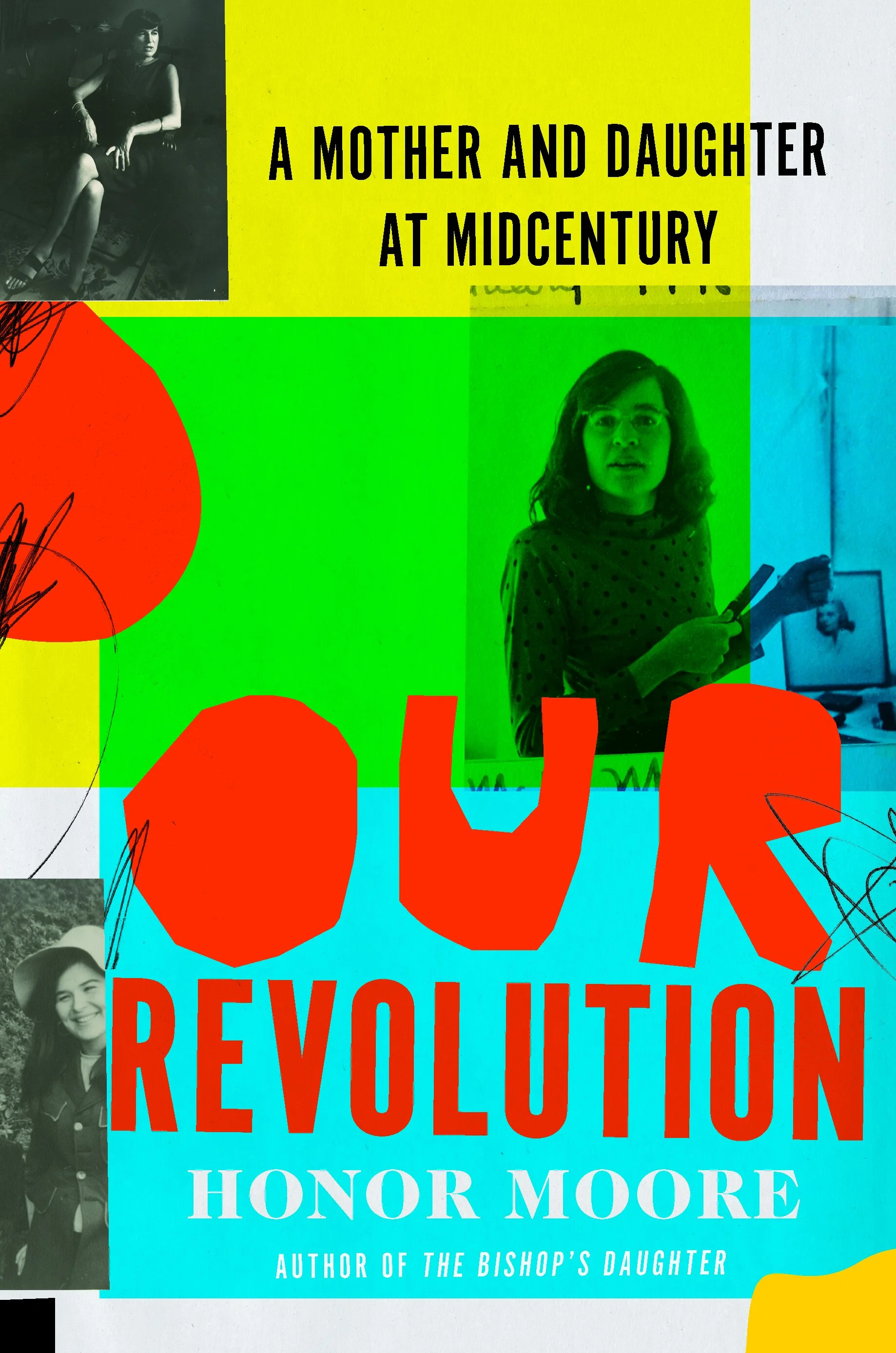

I read Honor Moore’s National Book Critics Circle award-nominated memoir The Bishop’s Daughter years ago, admiring the hybrid form that mixed the emotional excavation of memoir with the meticulous research of biography. So when Our Revolution: A Mother and Daughter at Midcentury was published in March, I put it on my reading list.

Honor’s mother, Jenny, died of cancer more than forty-five years ago. She was a mother of nine (Honor, the first born), an activist, and a writer (her memoir The People on Second Street was well received by readers and critics alike and sold 25,000 copies.) In her will she left Honor her “unfinished pages, fragments of memoir, and other manuscripts,” yet for decades her daughter didn’t do much with the trove. It wasn’t until she was in her sixties that Moore decided it was “time to get to know my mother” and began poring over the raw material.

The result is Our Revolution. As with all of Moore’s memoirs (she also wrote The White Blackbird, about her grandmother) the work is heavily researched; there are 381 notes at the end, providing detail on quotes and dialogue. Moore is also a poet and there is much to enjoy in her word choices and turns of phrase. She describes her mother as having an “almost disabling” toothache, and a quote in the book from Moore’s own journal describes “rows of trees that curled over and closed at the top like a Gothic cathedral.” The book benefits from Moore’s persistence as a researcher—if there is someone with information on her mother’s life, she finds them, including an old flame in his nineties, who blinks at Moore “through rheumy eyes.”

Though mother and daughter bond over the women’s movement in the book’s later pages, Jenny Moore’s earlier activism centered around race and class. After all, she and her daughter both lived through the protests against the war in Vietnam, the killings of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Kennedys, and the rise of the Black Panther party. Of the assassination of MLK, Honor Moore writes, “in Washington, as in many other cities, grief at King’s murder turned to rage and people took to the streets,” and later details the use of tear gas and police “beating demonstrators” at an anti-war protest in Chicago. Reading this amid the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement against police brutality, I found myself once again considering the notion that nothing ever changes in this country, that America is never able to live up to what it claims it wants to be.

This helps give the book contemporary relevance, but Our Revolution spoke to me in other ways, too. My own mother died years ago, and, similar to Honor Moore’s experience, she left me her journals, letters, essays, and notebooks filled with quotations and existential pondering. Like Moore, it took me years to fully unpack the boxes, a decade slipping away before I gathered the courage to read it all front to back and try to make sense of my mother’s life.

Once I began to look, Our Revolution provided countless echoes of my own family. Jenny Moore sought a new purpose for herself only after she’d finished bearing children; my own mother divorced my father and blasted out of the family only after our nuclear unit was built. Jenny wanted to be a writer and felt she had something to say; my mother’s journals are littered with references to the book she wanted to write. Jenny had been the first woman in her family to go to college; my mother the first person in her family, period, to go beyond high school. And of course both were drawn to the feminist cause—for Jenny Moore, reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was “a bolt from the blue”; for my mother, it was Adrienne Rich’s Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying that turned her inside out. The deeper I read, the more similarities I found, until I began to latch onto even the smallest, most ridiculous details, such as both Jenny Moore and my mother having “thick hair.” I was left marveling at the threads between these two women from very different backgrounds born some thirty years apart.

That similarity reveals something about women’s universal, timeless struggle for equality, but it also says something about Our Revolution itself. The specifics Honor Moore dug out about her own family left me reviewing my own, and the details of her mother’s life caused me to reconsider what I truly know of my own mother. Which is to say that Our Revolution, in the end, turned me inward, as literature is meant to do.

Brady Huggett’s work has been placed in Verbsap, Liar's League, and Fredericksburg Literary & Art Review, and he’s published a novella with The King's English. He is an award-nominated journalist and host of the podcast First Rounders.